LVT – FOUND AND LOST

Why was a successful LVT system abandoned?

- General background

- Inception, growth and decline

- Aftermath

- Conclusions and comment

- Appendix 1. Neoclassical economics

- Notes

1. General background.

Before embarking on the story of LVT in Pittsburgh it is necessary to say a few words about the structure of taxes generally in the USA. To an outsider the US tax system would appear quite complex and onerous. There are federal taxes and state taxes before getting to local taxes.

Although federal taxes are applied universally, states have considerable freedom to decide which taxes to impose, and to what degree. Below this level, local taxes may be imposed by counties, cities, school districts, utility districts and also special taxing authorities. Each state may set its own rules on how the local taxes are imposed, but each local jurisdiction has considerable autonomy to democratically decide its own affairs. Local revenues are mainly derived from property (real estate) taxes and to a lesser extent local income taxes (wage taxes). LVT falls within the description of a property tax. Property tax rates are determined through valuations or assessments. Where assessments combine the land and building values, this is known as a ‘flat rate’. Where the land and building values are assessed separately, this is known as a ‘split rate’. In either case these values are used to set ‘millage’ rates to determine the tax level for each household or commercial property (see box 1).

Box 1 Millage Rates

In the US, local property taxes employ the millage-rate system to calculate the taxes due. One mill is one dollar per thousand of the value of the property. So a property of value $100,000 with a millage rate of say 5 mills would pay a tax of $500 per annum, 6 mills, $600 per annum, and so on. Each jurisdiction with a claim on the property tax may set its own millage rate, decided annually by its finance director, who is charged with determining the level of the rate in accordance with the revenue requirements of the jurisdiction. The taxpayer is therefore obliged to pay a tax, which is the sum of all the various millage rates of different jurisdictions added together. In the case of the city of Pittsburgh, where the split rate was employed, there were two millage rates, one for the land value and one for the building value in which, since the law of 1913, the land value rate had to be twice that of the building value rate regardless of the level at which the rate was set. This lasted until 1979, when the ratio was increased. Property values could be ‘real’, ‘assessed’ or ‘fractional’, and so it is not too difficult to imagine how this complexity, combined with the millage-rate system, could result in a situation susceptible to manipulation and political interference.

Every property valuation necessarily comprises two factors, the value of the building (or improvement) and the value of the site upon which the building stands. A 100% pure land value tax taxes only the site-value factor and disregards the building value. A flat-rate tax makes no distinction for the land factor. Several cities, especially in Pennsylvania, have elected to apply the split-rate property tax in which the site-value factor is taxed at a higher rate than the building-value factor––effectively a partial land value tax. It is this system that Pittsburgh legislated to adopt in 1913, and which became known in Pittsburgh as the ‘graded tax’. The graded tax was to bring many benefits to Pittsburgh over the next 87 years, but was nevertheless rescinded in 2001. In a paper written in 2006, Mark Alan Hughes notes,

Pennsylvania is the only state government in the US to enable split-rate property taxation among its local governments. Since 1913, Pennsylvania has produced a body of sustained outcomes across 33 municipalities: 16 that have current split rates, 5 that have rescinded split rates and 12 that have considered but never implemented split rates.1

It should be noted that in October of 1913 the federal income tax was also introduced, and so we see the arrival at the same time of two major tax systems, one federal, one local. In the early years of the Union the states derived revenue mainly from property taxes, whereas federal revenues were largely derived from customs and excise duties and the sale of land, except in times of war, when additional taxes were imposed. After the war of 1812 Congress raised additional money by issuing treasury bonds.2

Income taxes

In 1861, during the Civil War, Congress introduced a temporary income tax. In 1862 further legislation allowed for its collection at source (an early form of PAYE?).3 After the war the need for federal revenue diminished and in1872 the income tax was abolished. It was revived again in in1894 4 but in the following year was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.5 This ruling was overturned in 1909 by the passage of the 16th amendment, which was ratified in 1913, enabling the introduction of the modern income tax, virtually co-incident with the Pittsburgh graded tax, which actually began on 1st January 1914. Income tax was to become one of the main sources of federal and state revenue thereafter, but even as late as 1918, only 5% of the population paid income taxes. In 1939 4 million paid income taxes and by 1945 this had reached 43 million.6 Although the income tax was initially only applied at federal level, it quickly became popular with politicians, and eventually was adopted quite widely by states and at local level by counties and cities. Another tax which became popular with politicians was the sales tax, which was also adopted in later years, at state level.

Local taxes

At the local level property taxes remained the main source of revenue and although never popular, these were accepted as the most appropriate way of taxing wealth and the ability to pay. Referring to the early years when property taxes were becoming established, Glenn Fisher notes,

In a simple rural economy wealth consists largely of real property and tangible personal property – land, buildings, machinery and livestock. In such an economy, wealth and property are the same things and the ownership of property is closely correlated with income or ability to pay taxes.7

But the land factor of the early property tax was measured according to acreage rather than actual land value, giving rise to a growing sense of unfairness. Fisher also notes that ‘Settlers far from markets complained that taxing land on a per-acre basis was unfair, and demanded that property taxation be based on value.’ 8

Even at this early stage there was an awareness of the value of location, which of course is now the main justification for urban land value taxation. So land was taxed indirectly as being part of the total property value of land and buildings combined. This had always been the case with the old ‘rating’ system that had applied in Britain from the 17th century and continues to the present day in the form of Council Tax. The rating system does not recognise that the relative proportions of site to building value varies over time, according to the growth or decline of communities. It is a fact that in rural situations, on any particular piece of land, buildings and improvements account for a much larger proportion of the value than the site. As a community grows and urbanises this proportion tends to reverse and the site value may often exceed the building value, especially where the buildings are older and less efficient. Where the site is subsequently developed with a new building the building value may again exceed the site value. Buildings and developments are visible and therefore perceived by most people as representing wealth, the higher the building the wealthier the owner, so on the principle of ability to pay, buildings are the more obvious targets for taxation. This rather simplistic view is often adopted by those opposed to LVT. In a leaflet opposing the new graded-tax act, distributed by a repeal movement in 1915, the claim was that: ‘Only the owner of the skyscraper is benefited by the act.’ 9

People are rarely able to see that the height of the building is usually proportional to the value of its location, although this is not necessarily always the case. Thomas McMahon, the Pittsburgh Chief Assessor from 1925 to 1934, claimed that ‘A vast majority of the best paying business sites in the city of Pittsburgh have buildings that do not exceed four or five stories’.10 However the former perception suited the large landholders and speculators who knew instinctively that increasing property values were due to the increased land (location) value that arises from economic expansion within growing communities. In his chapter in Land Value Taxation Around the World Walter Rybeck notes,

After the civil war era, economists, officials and citizens generally seemed overcome by amnesia about the importance of land and land taxation. Families of wealth and corporations on the contrary, far from losing sight of the land, accelerated their ownership of the nation’s natural resources and prime urban sites.11

From the earliest years the governors of the newly united states were aware of the evils arising from large landholdings that were characteristic of the old world. The Homestead Act of 1862 was an attempt to counter this threat. Rybeck also notes, ‘This act, signed by President Lincoln, enabled families to get 160 acres of free public domain land. By building a home and working the land for five years, they acquired title.’ 12 Also, ‘Until the 20th century, the property tax was virtually the sole support of state as well as local government.’ 13

In later years state governments reduced their reliance on property taxes, tending instead towards sales and income taxes, a tendency that ‘reflected the power of landed interests in state legislatures.’ 14 State property taxes, as a percentage of total taxes declined from 52% in 1902 to 2% in 1992. Local property taxes also declined, but to a lesser extent – from 88% to 75% over the same period (with a peak of 97% in 1922).15 In the cities the property tax remained the mainstay of tax revenues, although in later years the wage tax and sales taxes became another source. A paper, in 1995, by Howe and Reeb states,

Most of the relative decline since the 1930s in the property tax share of local government tax revenue nationally, has resulted from greater reliance on local general sales and income taxes, especially for counties and large cities. Local general sales taxes, first adopted in New York City (1934) and New Orleans (1936), came after rising discontent over property tax increases accentuated by foreclosures.16

Also it records,

Local income taxation first emerged in Philadelphia (1938), St Louis(1948), Cincinnati (1954), Pittsburgh (1954) and Detroit (1962).17

In the latter part of the 19th century great advances were made in industrial technology and the production of material goods, but the benefits of this productiveness were not equally shared within the population. Labour was exploited and unprotected by any organised form of state or national welfare. Many were rendered impoverished by the industrial progress and the laissez-faire attitudes that prevailed. This was the period of the great industrialists, the so-called ‘robber barons’, whose accumulations of wealth and power enabled them to exert influence over political policies at all levels of government. This led inevitably to every kind of graft and corruption. Laws were passed that only served the interests of industrialists and businessmen; the ordinary workers, a great many of whom were new immigrants, were ruthlessly exploited and their attempts to organise or protest were brutally suppressed by employer’s private police forces that had been enabled through legislation at state level.18 ‘During labour disputes the courts consistently ruled in favour of employer’s over worker’s rights.’ 19

The whole attitude of authority was in support of the ‘wealth creators’, who were seen to be the great industrialists like Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Rockefeller and J. P. Morgan, who made their fortunes through railroads, steel, oil and banking respectively. Anything or anybody that stood in the way of this process was swept aside. Economic depressions occurred with dismal regularity. Those of 1873, 1884 and 1893 caused great hardship in Pittsburgh and many other cities, many labourers becoming dispossessed vagrants. This was the period when Henry George was engaged in his work and gathering materiel for his book Progress and Poverty, which was published in 1879 and in which he observed, ‘Amid the greatest accumulations of wealth men die of starvation, and puny infants suckle dry breasts.’ 20

The problem of increasing poverty was widespread throughout the industrialised US. In his article ‘Why Pittsburgh Real Estate Never Crashes’, 21 Dan Sullivan lists several examples of the hardships that were suffered and in one case describes an army of unemployed that, in 1893, started a march on Washington from western Ohio, ‘Their ranks nearly doubled when they passed through Pittsburgh and Homestead.’ 22

The situation inevitably gave rise to a reform movement in which socially conscious politicians and progressive economists advocated commercial and fiscal reforms (including land value taxes) to combat rampant land speculation and monopolies. The Sherman anti-trust act of 1890 was passed to deal with the deliberate formation of monopolies by the growing numbers of unscrupulous and avaricious industrialists. Although Pennsylvanian politics was dominated at this time by the Republicans, there were both Republicans and Democrats within the growing reform movement. The introduction of the Pittsburgh Graded Tax was part of this movement.

2. Inception, growth and decline.

In his paper of 2005, Mark Alan Hughes refers to an article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette which recalls that in 1753, George Washington noted the potential of what was to become the downtown area of Pittsburgh, known later as the Golden Triangle, an area of land ideally placed between the confluence of the Monongahela and Allegheny rivers. Several of Washington’s military officers saw the same potential and bought tracts of land, which later became the ‘foundations for great fortunes.’ 23 After the Civil War Pittsburgh expanded through annexations of surrounding jurisdictions and its economic base increased accordingly. It industrialised rapidly to become one of the great centres of manufacturing, especially in the steel industry. Great wealth was created but unfortunately not equally shared amongst the population. Property taxes were imposed and to some extent the significance of location was recognised in that a system of classification was devised in relation to where a property was situated, and the tax abated accordingly. Three property classifications were established:

- Full City––attracted the full tax

- Rural (suburban) had an abatement of one third

- Agricultural had an abatement of one half

The (perfectly reasonable) theory being that the more urban areas enjoyed better services and therefore should pay higher taxes. The problem with this system was that the classifications remained fixed regardless of changes as the economy developed and the surrounding areas became more urbanised. The rural and agricultural sites became more valuable through being effectively under-taxed. The system became corrupt and led to a widespread sense of unfairness.24 However it continued until 1911, during which year the Pittsburgh Civic Commission recommended its abolition and the introduction of a law fixing tax rates on buildings at 50% that of land. This set the conditions for the future graded tax. 25 The commissioners saw that the great landholders ‘were impeding the city’s progress by holding the land at prohibitive prices.’ 26 An Article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette of April 2001, records,

From 1880 to 1910, the value of taxable real estate in the city rose from $99.5 million to $784.8 million. The price of land as a result became second only to New York’s, according to a 1912 study by the Pittsburgh Civic Commission.27

The graded tax was designed to constrain land speculation as much as it was to raise revenues. The pre-1913 reformers were very aware of the problems of land monopoly and speculation. Dye and England note that the tax ‘was motivated by the widespread perception in Pittsburgh that wealthy landowners were withholding land from development and realising hefty speculative gains.’ 28 As early as the 1870s there was great awareness of the negative effects of land speculation. Dan Sullivan records that in 1872 the president of the Pittsburgh Common Council complained of ‘The great landholders and speculators and the great estates, which have been like a nightmare on the progress of the city for the last thirty years.’ 29

After the Civil War Pennsylvania and Pittsburgh had become Republican strongholds, (the Democrats in Pennsylvania had lost a lot of credibility in backing the southern states), and this situation was maintained, with a few rare exceptions until the 1930s. The Republicans gradually consolidated their power and established control in Pittsburgh (and Philadelphia) through what came to be known as ‘city machines’, maintained through graft and favouritism. It has to be said that in other states and cities the Democrats ran equally corrupt systems, such as the ‘Tammany Hall’ organisation in New York State. Throughout this period Pittsburgh was growing rapidly, economically and geographically––the adjacent city of Allegheny was annexed in 1906. By the first decade of the 20th century Pittsburgh had become one of the greatest generators of wealth in the country, but had also gained the reputation of being one of the most corrupt, run by city bosses in league with corrupt politicians and big business interests. The graft and corruption that was widespread in Pennsylvania, perhaps had its ultimate manifestation in Pittsburgh under the political boss Christopher Magee, who together with his partner William Flinn ran the Republican party machine for the last 20 years of the 19th Century. In 1903 the investigative journalist Lincoln Steffens published a highly influential book The Shame of the Cities in which he castigated Magee’s administration and commented, ‘Pittsburgh is an example of both police and financial corruption.’ 30 In an article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette of March 21st 2010 the journalist Brian O’Neill reported that ‘For two full generations, almost without a break, the city was in the grip of one or another faction of the most cold blooded and vicious political rings that ever ruled an American city.’ 31

On the other hand Magee achieved many improvements in infrastructure, which benefited the city, so for some he was a great benefactor. At the same time a serious reform movement had arisen from the activities of well meaning, socially conscious politicians and philanthropists, both Democrat and Republican, amongst whom were the Georgists. The Explore PA History website notes that ‘Prominent members of the Republican party also broke with party leaders and attempted to reform the party from within, or by creating a third party.’ 32

In 1907 the Russell Sage Foundation funded a social survey that revealed the terrible situation that obtained in Pittsburgh at that time. Published in 1908 it clearly played a large part in raising public consciousness and influencing the decision makers. Following the report of the Pittsburgh Civic Commission in 1911, William Magee (nephew of Christopher, but obviously with quite different social mores; twice republican mayor of Pittsburgh, from 1909-14 and 1922-26), abolished tax breaks for large estates and also taxes on machinery. At the same time the old property classification system was scrapped. Magee was also persuaded of the merits of the Georgist idea after having investigated the successful experience of Vancouver where, in 1910, they had exempted all buildings from tax.33 Thereafter he became a keen advocate and spearheaded the legislation for a split-rate tax that was passed in 1913. In this year the State of Pennsylvania, led by the Republican Governor John K. Tener, passed an enabling act allowing cities of the 2nd class to apply a two-tier tax on property. This was duly adopted by Pittsburgh and Scranton and the tax came into force in January of 1914.34 Magee was a strong advocate for the graded tax and in 1915 he expressed his concern about,

The unearned increment, the profit of the landowner who becomes rich through growth of the community without effort on his own part. I am frankly opposed to him. He is a parasite on the body politic.35

The graded tax was introduced at a time when the Georgist movement was at its height, not only in the US, but throughout the world. At that time Georgist ideas were widely discussed and no doubt well understood by the reformers who got the legislation passed.

In Pennsylvania, cities are classified according to the size of population as 1st, 2nd, 3rd or 4th class. In 1913 the only 1st class city was Philadelphia. The only two 2nd class cities were Pittsburgh and Scranton. The planners of the Pittsburgh Graded Tax very sensibly decided that, to avoid disruption and reduce the grounds for opposition, the tax change should be introduced over a twelve-year transition period in five increments, in order to achieve this, arguably quite modest differential of 2 to 1, where the site was taxed at double the rate of the building. It was through this gradual introduction that the tax came to be known as the ‘graded tax’, and which no doubt enabled it to survive and prove its worth for many decades after its full implementation in 1925. Re-assessment of values continued to be carried out every three years by city assessors, as was already the custom for the existing flat-rate tax. From the outset, despite the small increments, the effect of the new tax rates were felt, especially in encouraging building activity.36 But at the same time opposing interests led by the great landowners immediately organised an opposition in order to repeal the new law.37 Those who had a vested interest by virtue of their ownership or control of land rents were not going to surrender their advantage without a fight. Mark Alan Hughes notes,

It was quickly challenged by the new mayor elected in 1914, (Joseph G Armstrong), the chamber of commerce, powerful landholders and politicians who said that the tax discriminated against landowners and was ‘unlawful, unjust and un-American’ 38

In 1915 Armstrong supported the passage of a repeal bill in the Legislature, but the situation was rescued, on appeal, by the Republican State Governor Martin Brumbaugh, who ruled that the graded tax law should be allowed to proceed. In the years that followed opposition to the scheme never went away. Throughout the period of its operation there were always critics and commentators who presented arguments as to why it did not or would not work, despite all the evidence to the contrary. On the other side of the argument there were strong supporters. The graded tax was helped in the early years by the presence of politicians and administrators who had Georgist sympathies and who held strategic positions within the administration, for instance Thomas C McMahon, who was City Chief Assessor from 1925 to 1934. It was McMahon who, after a trip to Vancouver, had recommended LVT to mayor Magee in 1911. Also Percy R. Williams (quoted frequently in this essay) was executive secretary of the Pittsburgh Real Estate Board from 1918 to 1921, a member of the city Board of Assessors from 1922 to 1926, and from 1934 to 1942 Pittsburgh’s Chief City Assessor. From 1926 to 1978 he was secretary and trustee of the Henry George Foundation.

Dan Sullivan comments, ‘Support for taxing land values rather than buildings remained so strong in the City of Pittsburgh that efforts to repeal the policy consistently failed.’ 39 Over the next 25 years the graded tax became embedded and operated successfully without serious opposition. In 1930 Thomas McMahon, commented, ‘So far as I can learn, no serious objection is offered to the present tax plan.’ 40 It also helped Pittsburgh to survive the great depression of the 1930s in that it did not suffer the severe collapse of land values experienced by many other cities; the existence of the higher tax on land had constrained the escalation of prices that had taken place elsewhere in the 1920s. Sullivan notes, ‘Pittsburgh was spared the added problem of a real estate crash because its graded tax had discouraged speculators from bidding up prices during the previous boom.’ 41

In 1934 the pro-LVT Democrat William McNair was elected mayor, so ending nearly 70 years of Republican domination of Pittsburgh’s politics. Prior to his election there had been an attempt to increase the graded tax ratio to 5:1, but this had been narrowly defeated in the General Assembly,42 McNair was a keen supporter of the graded tax, and organised various activities to educate the general public to the virtues of the split-rate system.43 So up to the advent of World War II the graded tax enjoyed much support at the level of local government. Thereafter this advantage diminished as the years progressed and over time the basic Georgist ideas became largely forgotten, except by the ardent supporters, so that by the end of the century the graded tax was seen by the general public as ‘just another tax’.

The early success of the graded tax was undoubtedly tempered by the concurrent introduction of the income tax in 1913, which became a competing factor for the attention of politicians constantly seeking ways of raising revenue. Although the initial application was at the national level, the income tax grew in influence at all levels of government, federal, state and local, becoming eventually the dominant tax, not only in the US but throughout the world. But it also had the effect of undermining the Georgist movement from the start. At a Council for Georgist Organisations conference in 2013, Alex Wagner Lough suggested that ‘Passage of the income tax marks the decline of the Georgist movement and might have caused it.’ 44 It certainly caused a schism in the Georgist ranks––Henry George was always opposed to it. But despite his formidable powers of persuasion in promoting the land value tax throughout the world, his arguments did not, in later years, dissuade his own son from supporting the Income Tax bill through Congress. Dan Sullivan notes, ‘Wilson’s administration, awash with Georgist leaders, proposed the 1913 income tax, and Congressman Henry George Jr. co-sponsored the legislation.’ 45 This schism did not help the Georgist cause, but nevertheless legislation for the graded tax survived the difficulty.

Another negative influence that has to be mentioned was the current neoclassical movement in economics that dominated academic thought throughout the period of the graded tax. The neoclassical economists saw land as just another form of capital and were totally opposed to the idea of land value taxation. (see Appendix 1) They were always in the background and ready to give support to any manifestations of opposition to the graded tax. In the Pacific Standard News website of October 2009, a pro-LVT contributor, in a discussion of Henry George, noted, ‘He’s been out of favour for decades, especially in graduate schools. Economists are trained to ignore him.’ 46

Nevertheless the obvious benefits of the split-rate property tax continued to be recognised and appreciated as much for its results as for its Georgist principles. The split rate was adopted later by many smaller towns in Pennsylvania. In 1951 the state legislated to allow cities of the 3rd class to use the split-rate system and this option was taken up by Harrisburg in 1975, McKeesport, Newcastle, Duquesne, Washington, Aliquippa, Clairton and Oil City in the 1980s, Titusville in 1990, Coatsville, Du Bois, Hazleton and Lock Haven in 1991 and Allentown in 1996.47 Not every city made a success of it. The failures were generally for reasons of bungled administration or inadequate valuations, but those that succeeded showed considerable benefits. The split-rate tax received many accolades from journalists and administrators during its time, some of which are recorded here. Admittedly some are from overt LVT supporters, but that does not make them any the less true. Dan Sullivan records that, as early as May 1915, the Pittsburgh Press reported, ‘The law is working to the complete satisfaction of everybody except a few real estate speculators who hope to hold idle land until its value is greatly increased by improvements erected on surrounding territory.’ 48 Williams, in his 1955 essay on Pennsylvania, records a comment in the Pittsburgh Post of 1927:

Formerly land held vacant here was touched lightly by taxation, even as it was being greatly enhanced in value by building around it, the builders being forced to pay the chief toll, almost as though being fined for adding to the wealth of the community. Now the builders in Pittsburgh are encouraged; improvements are taxed just one half the rate levied upon vacant land. Building has increased accordingly.49

In an address to an LVT Conference in London in 1936, Dr John C. Rose also claimed that the graded tax stabilised Pittsburgh’s municipal credit; ‘A stabilised credit is a wonderful asset to any city or community.’ 50 On the issue of land speculation, in his 1963 paper Williams claims,

‘Land speculation is no longer a major factor in Pittsburgh.’ 51 He goes on to list a whole range of 27 well-known national magazines that had published favourable articles between 1946 and 1960.52 Sullivan adds,

‘Every one of the 19 land-taxing cities in Pennsylvania enjoyed a construction surge after shifting to LVT, even though their nearest neighbours continued to decline.’ 53 In their definitive 1996 study Oates and Schwab suggested that ‘The Pittsburgh tax reform, properly understood, has played a significant supportive role in the economic resurgence of the city.’ 54

Although most of the examples of Pittsburgh’s success are related to the revival of the central business district and other downtown areas, there was also a beneficial effect on out of town residential areas where site values were lower. Williams makes the important point,

It is the homeowner who emerges as the chief beneficiary of the graded tax. This is widely recognised as one of the principal reasons why this plan has popular support. Only in rare instances do we find a homeowner paying a higher tax under the graded tax. The typical homeowner’s investment is largely in building rather than land, it being quite common for the assessed value of the house to be as much as five times the value of the site, and often this ratio is exceeded. 55

Perhaps the high point was in 1998 when, at federal level, legislation by the Senate and the House was passed to allow the two-rate system for nearly 1000 boroughs in Pennsylvania. But despite this apparent confirmation of success, within three years the Pittsburgh two-rate system would be rescinded. So what went wrong with the graded tax? How can one account for this sudden reversal of fortune. Hughes makes the cautionary comment, ‘The 2001 abandonment of the split-rate in Pittsburgh is a compelling example of the limited role that evidence often plays in policy decisions.’ 56 As with many political changes the causes often have a long gestation period, and I suggest this was the case with the split-rate tax in Pittsburgh. Perhaps the turning point in its fortunes began as early as 1942.

By the late 1930s the costs of making assessments had become a contentious issue. The County of Allegheny already made its own flat-rate property assessments for county and school taxes, and the issue was over the apparent waste due to duplication of resources. The proposition was to make economies by transferring responsibility for all assessments from the city to the county. The city assessors, who were generally in favour of the split rate, resisted being taken over, but after some years of argument the county, who were generally against the split rate, prevailed and the change was made in 1942.

Although on the face of it the 1942 switch of assessments to Allegheny County would appear to have been a reasonable and logical step, it may have marked the beginning of the weakening of support that had maintained the graded tax hitherto. The city assessors had only the graded tax to deal with and had become highly skilled in its administration. Williams states that ‘Between 1922 and 1942 the City of Pittsburgh succeeded in establishing a fairly high standard of evaluation for both land and buildings.’ 57 In contrast, the county assessor’s experience had been limited to the flat-rate system, for county and school taxes and it is likely there was a loss of expertise in handling the new situation. Also Sullivan asserts there was downright hostility to the tax: ‘Responsibility to assess land values was shifted to the county, where opposition to LVT was stronger and support weaker.’ 58 Also, ‘Opponents of LVT dominated the county board of assessors.’ 59

As early as January of 1943, after the first new county assessments, the Pittsburgh Press reported on an enquiry called at the request of the County Commissioners, who had received complaints from taxpayers about the new assessments being ‘unfair and inequitable’. One of the tax board assessors made the charge that ‘The assessments are being altered to suit political expedience.’ 60

Sullivan again notes,

County assessors gradually came to ignore land values, keeping those the City assessor had put in place and putting subsequent changes onto building values whenever possible. 1980 assessments were a fairly accurate reflection of 1950 land values.61

He goes on to describe how certain wealthy neighbourhoods had their land assessments reduced, whilst poorer neighbourhoods continued to be over-assessed. He comments that ‘This marks the point when county assessors crossed the line from neglect to overt malfeasance.’ 62

further weakness of the assessments system from 1942 onwards, was the reliance on the so-called ‘base year’, which was the somewhat arbitrary selection of a particular year upon which to base subsequent assessments. Naturally, the longer the time scale extended from the base year the less accurate the assessments became (even assuming the base year values were themselves accurate).

During World War II, Pittsburgh enjoyed a temporary boom with the increased demand for steel but after the war the demand was drastically reduced and, as with many industrial cities, Pittsburgh was facing an economic decline. There was an inevitable move away from heavy industry towards more commercial and ‘white collar’ activity. In 1940 manufacturing had accounted for 50% of employment but by 1980 this had declined to 25%, and only 16% in 1985. The population declined from over 700,000 in 1950 to 400,000 in 1980.63 These figures were typical of all the large industrial cities of the North East.

To counter this decline, in 1946, Pittsburgh initiated ‘Renaissance 1’, a construction programme using low interest rates and tax abatements for investors, to encourage redevelopment. Many other cities elsewhere in Pennsylvania and other states also introduced similar schemes, which offered property tax relief for new construction, for anything between 10 to 30 years.64 However, unlike Pittsburgh, these only applied to the flat-rate systems in use and although they had considerable benefit for many cities, they did not have the additional advantage of the split rate. Also they had a negative effect by causing resentment amongst enterprises continuing to operate in the existing older buildings which, being excluded, saw themselves as effectively subsidising their competitors.65

Together with the advantage of the graded tax, Pittsburgh experienced a construction boom without a real estate price boom.66 This positive development compared favourably with the continuing decline in other industrial cites, and did not pass unnoticed. In 1960 ‘House and Home’ the construction industry’s leading trade journal quoted the Pennsylvania Governor and former mayor of Pittsburgh from1946 to 1959, David Lawrence, as saying,

There is no doubt in my mind that the graded-tax law has been a good thing for the city of Pittsburgh. It has discouraged the holding of vacant land for speculation and provided an incentive for building improvements. It produced a more prosperous city.67

Whereas many old industrial cities struggled to halt the decline in their fortunes, Pittsburgh became known throughout the USA as a city that had best been able to cope with the problems, demonstrated by its continuing building activity and avoidance of dereliction, especially in the central city areas. Rybeck notes that ‘Pittsburgh thrived with its two-to-one land-building ratio. After World War II, despite the decline of its steel industry, Pittsburgh enjoyed a renaissance.’ 68

Perhaps for this reason enthusiasm for the split-rate idea continued in Pennsylvania. In 1951 the State legislated to allow for the split rate to be adopted by 3rd class cities and at the same time abolished the 2:1 ratio limit. Also as late as 1998, a law allowing the split rate to be extended to boroughs was passed by Governor Thomas Ridge. However with increasing demand for more infrastructure and services local authorities were in constant need of more revenue and in 1954, rather than increase the property tax, Pittsburgh introduced a Wage Tax.69 Percy Williams makes the point that by 1963 the split-rate tax accounted for only about half of all the property taxes paid by each householder; school, district and county taxes, which were on the flat rate, accounted for the rest.70 Williams enlarges on this in his 1963 paper, where he makes some interesting comments on the effectiveness of the graded tax. He points out that as the graded tax did not apply to county and school districts, its overall impact was reduced. He also notes that, where the graded tax was concerned, due to the changing relationship of land to building values over time, the proportions collected from each source changed accordingly. Of the total city assessments in 1914, land values comprised 63%, building values 37%. In 1960 the situation was almost reversed, with land values at 35.7% and buildings at 64.7% of the total. In the middle period 1929-39 the values were almost the same, so the 2:1 ratio during that period translated into 2/3 of revenue being raised from land, 1/3 from buildings. But by the 1960’s the share would have had to be more than 2/3 on land, and less than 1/3 on buildings to maintain the same amount of total receipts. This of course would be welcomed by the LVT purists who wanted a 100% tax on land, but at the same time it gave ammunition to the anti-LVT lobby who saw it as letting the wealthy building owners off lightly.

Mainly due to increasing worldwide competition, the economic decline of the old industries in Pennsylvania and other industrial states continued and led eventually to what became known as the ‘rust belt’. Pittsburgh was very much affected by the same problems and the ‘Renaissance 2’ programme was initiated in the 1970s to again help stimulate reconstruction activity, but perhaps the most significant decision to revitalise the city was the increase of the graded tax ratio in 1979-80, from 2:1 to 5:1.This move was enabled by much earlier State legislation that had been enacted in 1951 that allowed cities of the 3rd class to adopt LVT if they so wished and at the same time abolished the 2:1 ratio limitation imposed in 1913.This legislation indicated at that time a degree of support for the graded tax at State level, where the benefits were evidently recognised, even at the comparatively modest rate of 2:1. In 1979, in order to raise more revenue, the Democrat mayor, Caliguiri, had proposed increasing the wage tax (introduced in 1954), but he was overruled in the city council, led by William Coyne, a keen supporter of the graded tax, who instead prevailed upon the council to raise the graded tax rate to 4:1. Again in 1980, despite Caliguiri’s opposition, the rate was increased to 5:1. Caliguiri maintained his opposition to the split-rate tax and in 1985 commissioned a study from the Pennsylvania Economy League, which concluded that ‘the graded tax had very little effect on development’, also, ‘The benefits fall primarily on single-family dwellings in more affluent neighbourhoods.’ But the report was challenged by LVT advocates. They claimed it was biased, as the director of PEL, David Donahoe, had previously been Caliguiri’s budget director charged with providing arguments against LVT.71 Sullivan comments,

This study was so tortuously contrived and so easily refuted that the city council ignored it and continued shifting the tax burden to land values.’ 72

But no doubt the prestigious PEL. report had some influence on doubters.

In 1989 the wage tax was seen to be driving potential residents out of Pittsburgh and it was decided the tax should be reduced. To compensate for the loss of revenue, mayor Masloff’s finance director Ben Haylar, who was anti-LVT, proposed a flat-rate property tax increase on both land and buildings. But the City Council under Jack Wagner (pro-LVT), voted to put the bulk of the increase on the land factor, resulting in a 6:1 ratio. This increase was supported by mayor Masloff and various business organisations that had previously opposed the 1979-80 increases.73 So even at this late stage there was still strong support for the graded tax, but also growing opposition. Ben Haylar remained a vigorous opponent of LVT, and when he later moved to Philadelphia to work for the mayor there, he opposed moves to introduce LVT in that city, calling it ‘a really bad idea.’ 74

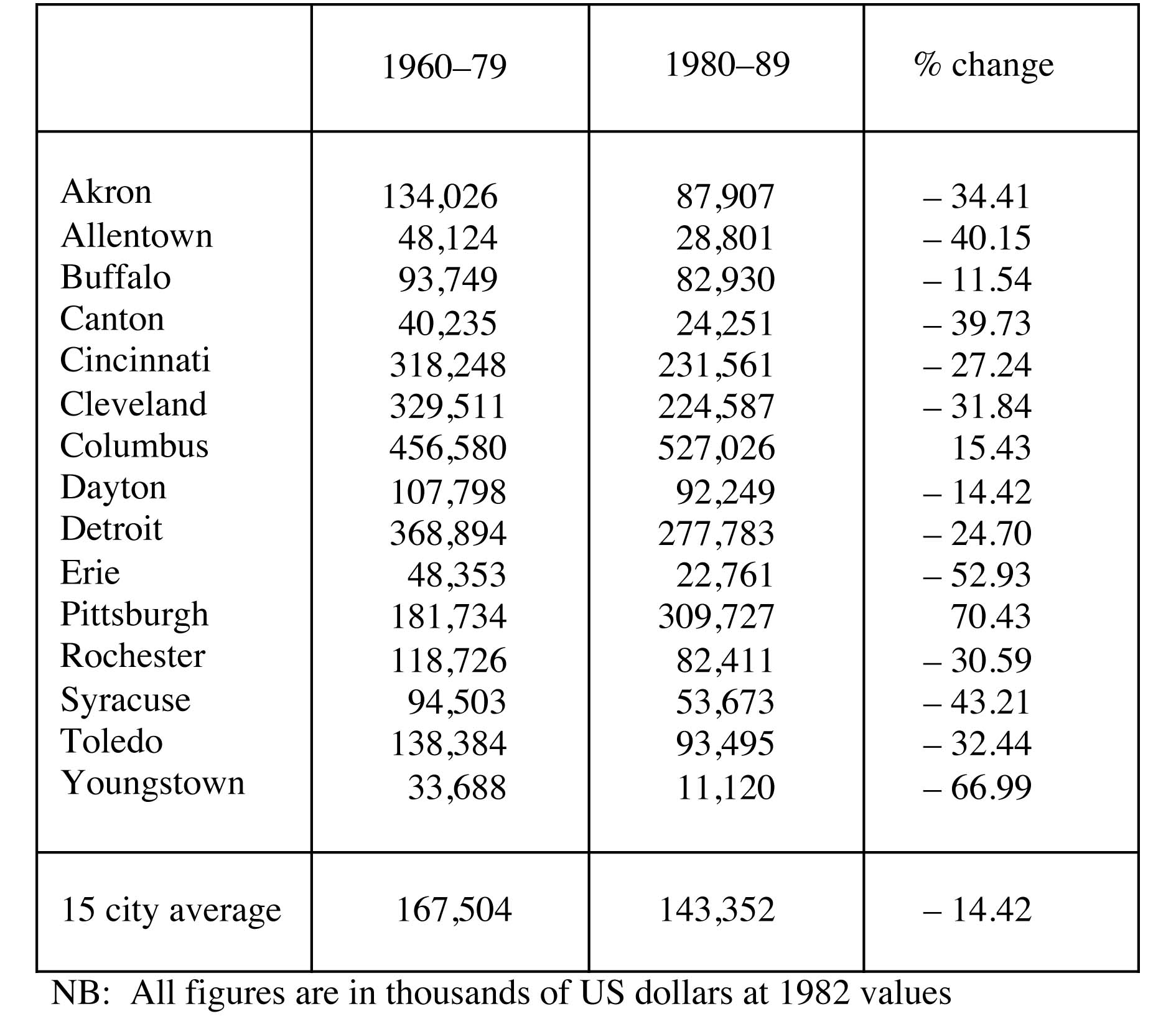

The change of ratio to 5:1 increased the penalty on land holders for keeping land out of use, and stimulated a further building boom, the results of which are well documented in a 1996 study by Oates and Schwab. The study compares the relative situations of 15 ‘rust belt’ cities in the period 20 years before and ten years after 1979, as measured by the value of building permits. (see table 1) (The value of building permits issued is taken as a measure of new building activity and therefore the prosperity of a community).

Table 1. Comparative list of average annual values of building permits. (Source: Table 3 of paper by Wallace E. Oates and Robert M. Schwab:‘The impact of Urban Land Taxation: The Pittsburgh Experience, JSTOR National Tax Journal, vol. 50,no.1,1997, pp. 1–21. www.jstor.org/stable/41789240)

Table 1. Comparative list of average annual values of building permits. (Source: Table 3 of paper by Wallace E. Oates and Robert M. Schwab:‘The impact of Urban Land Taxation: The Pittsburgh Experience, JSTOR National Tax Journal, vol. 50,no.1,1997, pp. 1–21. www.jstor.org/stable/41789240)

The results revealed that only Pittsburgh showed a large increase. Columbus, Ohio, also showed an increase, but Oates and Schwab suggest this may have been due to annexations of surrounding jurisdictions, that took place during the same period. The value of permits showed an average decline for all 15 cities of 14.42%, but a 70.43% increase for Pittsburgh (a 15.43% increase for Columbus). However, despite its obvious success support for the graded tax was beginning to weaken; Hughes notes that ‘By the late 1970s the consensus began to fracture.’ 75 But the main reason for the abandonment of the graded tax was the faulty system of assessments, which had become increasingly more dysfunctional in the decades prior to 2001. Hughes notes that in 1979

The assessments of both land and building values remained essentially fixed in this period, and indeed for the next twenty years.

Referring to Democrat mayor Tom Murphy, in office from 1994 to 2006, he comments that ‘For years Murphy had derided the chronic under-assessments.’ 76

The assessment system had been in place before the graded tax began in 1914 and was always dependent on the expertise and integrity of the assessors, who were charged with the task of making the assessments as close as possible to actual market values and also fair to all taxpayers. A clause in Constitutional and Statutory Provisions of 1912 states, ‘Property is to be assessed at its actual value, being the price for which it would sell.’ 77 Over the years, due to pressure from politicians promising ‘not to raise taxes’ there was always a tendency to make under-assessments, which led to an increasing disparity with actual market values, and perceived injustices amongst those who considered themselves over-assessed. Under-assessments of course also brought in fewer tax revenues. Another factor that needs to be taken into account was the existence of the fractional-assessment system. (see box 2) This system allowed taxing jurisdictions to apply only a fraction of the real market value for tax purposes. It applied to all property taxes, flat or split rate, and each county could decide whether or not to apply the option and if so, to determine its own rate. Although ostensibly it did not distort the fairness of the tax distribution between households, it became part of the problem that developed in the 1990s in Allegheny. Also its legitimacy was always in question in relation to the state uniformity clause. (see box 3)

Box 2 Fractional-Value Assessments

The fractional value assessment system, which operates to different degrees throughout the US for all property taxes, is one in which only a fraction of the assessed real value is used for tax purposes. It is against this reduced value that the millage rate is set to obtain the required revenue. If the fractional level were to be lowered then the millage rate could be raised to obtain the same revenue, and vice versa. Theoretically the fractional system does not distort the fairness of the tax as relative values remain the same, but there are many who criticise the system. According to the Chief Analyst of the Connecticut Office of Legislative Research, the fractional system began in the 1930s, when, due to the depression, real market values fell below the assessed values. When the real market values rose again after the war, the fractional system remained and became widespread normal practice.78 In another account, the fractional assessment practice goes back much earlier, and was always seen as contrary to the law. Bill Rubin, a former county assessor in New York state comments, ‘For two centuries properties were routinely assessed well below market value, in successful attempts to gain tax advantages for constituents’. He also asserts that the fractional assessment practice was contrary to existing law. ‘These illegal practices were ignored by both the legislative and judicial branches of government, which turned a blind eye to these flagrant violations of the law by the executive branch.’ 79 On a NY State website explaining assessments the comment is made, ‘It almost goes without saying that it’s very easy to be confused when assessments aren’t kept fair and at market value, and it’s also much more difficult to explain.’ 80

The law firm Flaherty Fardo list several cases from 1970 onwards of claims for unfair assessments and also note that in 1992 a computer aided survey of 500,000 properties found many were substantially ‘out of whack’ with their actual purchase price.81 In the same account they note, ‘In January 1994 an effort to address assessment problems resulted in substantial increases in property values – some more than 40% – leading to a taxpayer revolt’. The situation came to a head in 1996 when, after six decades of domination by the Democrats, the Republicans took control of the County Commissioners and immediately imposed a 5-year freeze on assessments, at the same time firing 42 assessors. This drastic action was opposed by Democrat mayor Murphy, who was vindicated the following year when the Common Pleas Judge R. Stanton Wettick Jr. declared the freeze illegal and ordered new assessments to be carried out, related to real market values.82 At the same time he ordered that the system of fractional assessments be abandoned. For this task Allegheny County, in 1998, hired a private firm, Sabre Systems and Services, to carry out county-wide re-assessments. Events developed rapidly from this point on.

Sabre Systems were appointed to carry out the re-assessments, not only for the graded tax, but all the county taxes, which included school districts, which used the flat-rate system. Sabre Systems were occupied for the next 27 months with this major operation, which resulted in an initial report in 2000, followed by the final report in 2001, both of which were badly handled by Sabre Systems, as described below.

In order that the city finance director could set millage rates for 2001, Sabre issued a preliminary combined assessment in 2000 anticipating that the land value share would be approximately 20% of the total. But this initial assessment did not reveal the previously gross under-assessments of the land factor. Hughes adds that ‘The problem arose in the millage rates the city had set based on the initial lower aggregate land value and this was further confounded (sic) by the move from fractional to full valuation.’ 83 The initial assessments were made public and led taxpayers to believe that the proposed future increases would be reasonable. When the final assessment notices were issued in 2001, showing separate valuations, the land element was much higher than had been indicated previously. In the year 2000-2001 the assessments for land value increased by 81% and for building value by 43%.84 These higher than expected tax demands caused much confusion and resentment and led to the eventual rescission. In a 2010 article on the Philly Record website, Steven Cord, a previous member of the city council recalls that ‘Well-to-do voters in Pittsburgh were suddenly aroused to fever pitch about their property tax as never before because a county re-assessment increased their land assessments from five to eight times overnight.’ 85 Bill Bradley writing on the Next City website in August 2013 noted one of the actions that brought the graded tax to an end, ‘The city’s unique tax structure was ended, as wealthy homeowners outmanoeuvred downtown developers and poorer residents to strike it down.’ 86

Hughes summarised the situation in saying, ‘The existence of the split rate made a bad problem worse and was processed as the cause rather than just a magnification.’ 87

Hughes describes in some detail the events that unfolded after the appointment of Sabre Systems in 1998. The following is a summary of three important points that, he suggests, led to the rescission in 2001:88

- The problem of the divided responsibility between city and county: The county assessors were also responsible for county and school district taxes, which were based on the flat rate. This of course had been the case since the transfer in 1942, but the split responsibility probably did not help in solving the later assessment problems concerning only the city-graded tax.

- The added complication that Sabre Systems carried out a re-assessment at the same time as trying to revise the system of fractional assessments to full market value. The fractional system allowed for assessments to be a percentage of full market value, which at this time were as low as 25%. The increase to full market value (required by the Wettick court order) in addition to the re-assessments caused large increases in many tax demands and widespread protests.

- The occurrence of a mayoral election contest, at the same time as the re-assessments in 2001––between the incumbent Tom Murphy who was pro-LVT, and his council president Bob O’Connor, who was anti.

The dispute between O’Connor and Murphy (both Democrats) at the time of the Sabre re-assessments is instructive. Both men were convinced they were on the side of justice and fairness. Murphy undoubtedly had a better understanding of the Georgist principles on which the graded tax was based, but O’Connor presented his case also as one of basic fairness. In the dispute Hughes records O’Connor as saying, ‘The people taking advantage of the two-tiered rate for the last 50 years, are the big office buildings. It’s to their benefit.’ 89 Also, ‘Large property owners have learned how to manipulate Henry George’s two-tiered system to the detriment of the poor and middle class of this city.’ 90 ‘Maybe years ago this system might have been able to work. But the only reason I can think of anyone fighting a single-rate system is only to protect the big boys downtown.’ 91

Perhaps with these statements, however well intentioned, O’Connor reveals his subservience to the ‘tax the high buildings’ shibboleth mentioned earlier, and his ignorance of the causes of land value. Sabre Systems were overtly on the side of O’Connor; their representative George Donatello commented on the split rate: ‘It’s a bad system and the taxpayers are going to pay for it.’ 92 Also a county board member, another O’Connor supporter, Jerry Speer, said, ‘People don’t care what their assessments are. They care what their taxes are. The one-tiered system is the only way to make this fair and equitable.’ 93 The public tended to be generally on the side of O’Connor – Dye and England note: ‘Public perception held that land values were relatively under-assessed for downtown Pittsburgh business interests and over-assessed for residential properties.’ 94

O’Connor wanted to abolish the split rate altogether, whereas Murphy wanted to keep it. Under pressure from all sides, Murphy proposed reducing the ratio to 3:1 as a compromise. But this was not sufficient to save the tax. The weight of opinion was in O’Connor’s favour, and eventually his view prevailed. Although everyone accepted that the defective assessment system was the main problem, the majority view was that the existence of the graded tax itself was to blame. Hughes notes that ‘After less than three and a half weeks of public debate, the venerable split-rate tax was gone.’ 95

3. Aftermath

The confusion over the property tax assessments continued after 2001, and to this day remains basically unresolved. Ironically the elimination of the graded tax, the supposed cause of the problem, made no difference to the ongoing crisis. In his ‘238 report’ Steven Cord records,

After it rescinded its land tax, Pittsburgh suffered a 19.5% decline (adjusted for inflation) in private new construction in the three years after rescission as compared to the three years before.96

Also,

A computer examination of the entire Pittsburgh assessment roll found that 54% of all homeowners paid more property tax with the rescission.97

The final Sabre assessments issued in 2001, gave rise to more than 90,000 appeals. Further assessments carried out in 2002 showed an average tax increase of 11%, leading to another 90,000 appeals.98 From this time onwards the Pittsburgh property assessments provided a battleground, not only between politicians but between politicians and the judiciary, represented again by Judge Wettick, who had to decide on the legitimacy of the various proposals made: freezes, caps and a reliance on base years. The county chief executive in 2002, Jim Roddey, a Republican, instituted another three-year freeze on assessments. In February 2005 the new assessments for 2006 would have resulted again in large increases for many homeowners, so the county controller Dan Onorato, who had replaced Roddey in 2003, proposed to cap any increases at 4%, but the following May Judge Wettick ruled the 4% cap to be illegal.99 However, in October of 2005 Onorato, in a change of tactics, decided not to use the revised assessments but to go back to using the 2002 assessments as a base year. Hughes comments that in this period, ‘Dan Onorato, by seeking to avoid taxpayer fury met by his predecessor Jim Roddey, has taken upon himself to try to control property taxes by manipulating assessments.’ 100

By the end of October two lawsuits by homeowners, who would have suffered losses, had been filed against the county, challenging the use of the base year. In 2007 Judge Wettick ruled that the law allowing the use of a base year was unconstitutional as it contravened the superior State Uniformity clause (see box 3). This ruling was, after an appeal in 2009, upheld by the State Supreme Court, which ordered a new assessment for 2012 and put Wettick in charge of the programme. In an article of June 2007, Mark Belko in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that ‘In his ruling, Judge Wettick estimated that at least 34 of 67 counties in Pennsylvania did not conduct a comprehensive assessment in the 20 years between 1985 and 2005.’ 101 Also: ‘Such a gap invariably leads to disparities, which judge Wettick said inevitably discriminates against homeowners in lower valued areas whose assessments remain high even as their property values decline.’ 102

On Jan 3rd 2012 Rich Fitzgerald, also a Democrat, was elected as county executive on the promise of not implementing the new assessments, which of course put him in conflict with Wettick. Wettick eventually prevailed but deferred the implementation until 2013. In 2012–13 the law firm Flaherty and Fardo reported that over 100,000 appeals were filed.103 The assessment crisis continues and is still unresolved.

Box 3 The Uniformity Clause

Uniformity clauses were introduced at both federal and state levels in the early years of the Union with the admirable purpose of ensuring fairness in matters of taxation, however the interpretation of the clause varied from State to State, and led to some uncertainty, but the law often seemed to work against the application of LVT. In a useful Wikepedia article on LVT, it is explained that ‘the exact wording and meaning of these clauses differs from constitution to constitution.’ Also, ‘Even in rather strict uniformity clause states, it is unclear whether the uniformity clause actually prohibits separate land value taxation.’ 104

Where it worked against LVT was presumably in the interpretation that taxing land at a different rate to buildings was not uniform. Rybeck mentions several instances of the uniformity clause being invoked or simply ignored depending on whose interests were being served. He notes the cases of Houston, Texas in 1912 and San Diego, California in the 1920s where buildings were taxed more highly than land; the uniformity clause was ignored.105 When attempts were made to reverse the ratios, the clause was invoked ‘at the behest of special interests.’ 106 Many US states say they cannot allow LVT without amending the uniformity clause in their constitutions. However, in 1913 Pennsylvania made the necessary amendment, which enabled the introduction of the graded tax. It is interesting to note that it was the uniformity clause to which Judge Wettick referred in his 1997 ruling to abandon the fractional assessment system and to carry out new real-value assessments. Also, where the base-year system was concerned, in his summing up he comments: ‘I find that Pennsylvania’s legislation, permitting assessments based on the use of the same base year indefinitely, violates the uniformity clause.’ Also, ‘Studies have shown that infrequent reassessments adversely affect assessment uniformity.’ 107

4. Conclusions and comment.

Some interesting comments by a lawyer involved in the 2011–12 re-assessments may help to explain the Pittsburgh property tax predicament. In an article written for the National Real Estate Investor, Sharon Di Paolo made the following observations:

Pennsylvania has no mandatory requirement for periodic revaluation, meaning that, as a practical matter, no county spends the time and political currency to reassess properties unless a lawsuit compels them to do so.108

Also,

Seven Pennsylvania counties have not reassessed in more than 30 years, and Blair county’s last reassessment was in 1958. The reason that Allegheny county is undergoing yet another reassessment is that multiple lawsuits have forced it to do so.109

Challenges to assessments are apparently nothing new. In the final paragraph she notes,

Governor William Penn announced Pennsylvania’s first property tax in 1683; within two weeks of the tax’s enactment, a property owner filed the first complaint challenging an assessment. More than 300 years later Pennsylvanians still struggle to find the right solution to meet Pennsylvania’s constitutional requirement of uniformity in taxation.110

It is notable that in two separate accounts, by independent journalists and lawyers, listing the sequence of events of the assessments crisis between 1996 and 2013, no mention is made of the disappearance of the graded tax. Perhaps such silence is the most telling obituary for the graded tax. An article of April 2012 by the Philadelphia Inquirer staff writer Anthony Wood probably sums up the general view of homeowners to property taxes: ‘When it comes to the real estate tax, opinion is deeply divided: Half of property owners hate it, and the other half really, really hate it.’ 111 Also Rybeck comments that ‘Unfortunately, the entire property tax, not just the tax on improvements, is constantly vilified.’ 112

Despite their unpopularity, property taxes seem to be a permanent fixture for local taxation regardless of competition from local wage taxes, which perhaps are disliked even more. People recognise that local services have to be paid for in accordance with the degree to which they benefit from such services, and also according to the ability to pay. Despite the arguments for or against any form of taxation, people are always aware of the issue of fairness. Traditionally the overall value of a property, combining land and building, the ‘selling price’, has been used as a measure of the ability to pay and a tax on a percentage of this amount, as mentioned earlier, is known as a flat rate. Regardless of how much the flat rate is disliked it has always been readily understood, not least because of its simplicity. Dye and England make the point: ‘It is harder for taxpayers to judge the fairness of assessments when land and improvements are valued separately.’ 113

The fact that the overall value of a property is a combination of the building value and the value of the site on which it stands is a subtlety that is not well understood. The fact that the building value is attributable to the owner and the site value to the community, even less so. The split- rate system depends on an understanding of this separation, which with the Pittsburgh graded tax, was established and maintained in the early years by the Georgist presence in administrative positions. When this presence became attenuated in later years the graded tax became more vulnerable to being misunderstood. An article in a 1983 issue of Fortune Magazine commented, ‘Few people, even among public officials and real estate executives, understand the nature of the tax and its economic ripples.’ 114 In his 1963 paper, even Williams admits, on the matter of the graded tax: ‘The ordinary citizen of the city, if questioned, is apt to reveal little, if any, knowledge of the subject.’ 115

One of the great advantages of the income tax is that people understand it. They also understand that it relates directly to the ability to pay and that it is progressive. The fact that it can be subject to abuse through evasion and gross avoidance, and is a discouragement to work does not seem to outweigh its advantage as far as acceptance is concerned. (although in recent years a growing worldwide movement has arisen to combat the scandals of tax havens and an avoidance industry, which are enabled by the nature of the tax itself). And so income tax and the flat-rate property tax have a considerable advantage over the split-rate tax in that they are more readily understood. LVT requires more initial explanation and a permanent system of education for its survival to be guaranteed. On the other hand there is no need for special educational measures to persuade people that ownership of land will enhance their wealth; they know it instinctively.

It seems clear from this account so far that the primary cause for the abandonment of the Pittsburgh graded tax was the defective assessments system and the inordinate lapse of time since the last real valuations. New assessments were simply based on previous assessments, going back to some arbitrary ‘base year’. Not for decades had a real market valuation been carried out prior to 2001. Certainly there were other causes: political interference, competition from the wage tax, the ever-present opposition from vested landed interests and the hostility of householders to any form of property tax. Politicians competed to reduce property taxes to get themselves elected. In an article entitled ‘Reorganising the Rust Belt’, Steven Lopez commenting on the Allegheny County flat-rate tax notes,

A Democratic administration cut county tax rates (millage) by 16%, in 1994 and enacted another cut of nearly 10% in late 1995. Republicans upped the ante, however, during the 1995 county election campaign, promising a further across the board property tax cut of 20%.116

It could be said that had the assessment system been properly administered, and recognised as essential to the correct functioning of any property based tax, split rate or otherwise, then perhaps the graded tax would still be in place today. Prior to 1942 the graded tax appeared to be well administered and did not provoke any untoward public protest or opposition. In the early part of the 20th century Henry George was a well-known and respected figure, and the Georgist idea of taxing land was accepted by many politicians and administrators, but by the 1970s his influence had waned and the anti-LVT sentiments were re-emerging. Although there were politicians on both sides of the argument, by the 1980s it was generally agreed by both sides that the assessment system was not working. In its 87 year history the tax operated with undoubted success for the first 28 years, and provided Pittsburgh with a stable property tax that saw it through the depredations of the 1930s. Between 1930 and 1940 Sullivan cites the fall in land prices of several comparable cities: ‘Detroit 58%, Cleveland 46%, Boston 28%, New Orleans 27%, Cincinnati 26%, Milwaukee 25%, New York 21% and Pittsburgh 11%.’ 117 These figures speak for themselves. Pittsburgh survived best because land prices had not become excessive during the boom years of the 1920s. The graded tax continued to have a beneficial effect well into the later years of the century. Sullivan mentions the closure of the Jones and Loughlin steel mill in 1979 and adds, ‘Even this didn’t prevent Pittsburgh from enjoying the biggest construction surge in its history. The real-estate editor of Fortune credited the LVT with playing a major role in Pittsburgh’s second renaissance.118 However, by the 1980s the damaging consequences of the faulty assessments became too evident to ignore; even as early as the 1950s there was an awareness that something was not right. Williams notes,

In 1957 Mayor David L Lawrence launched a campaign for a more realistic appraisal of both land and buildings in order to make sure that all taxpayers were fairly assessed and that nothing was permitted to hinder the proper functioning of the graded tax plan.119

Despite this initiative the disparity between assessed values and real market values continued to get worse. What was the reason for this? I would suggest four main reasons:

- Political interference.

- Negligent or biased assessment practices.

- The Fractional Assessment system.

- Costs of making assessments.

1. Political Interference

In the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette of June 2007, Mark Belko comments, ‘If history has shown anything, it is that county politicians will go to great lengths to avoid regularly re-assessing property.’ 120 Politicians at all levels of government, despite their protestations to the contrary, always want to be popular. They always have an eye on the next election. One of the ways of gaining popularity is by promising to reduce taxes. They do this in the hope that they will make up the shortfall by other means, usually unspecified––other than making efficiency savings or cutting out waste, in other words being better managers than their predecessors. The ordinary taxpayer is acutely aware of direct taxes such as income tax and property tax, less so of indirect taxes such as a sales tax. Politicians prefer indirect taxes because they can allow the people to believe they are not paying higher taxes, only higher prices. The property tax is an obvious target for tax reduction, and there is always a latent political pressure on assessors to keep assessments low or certainly not to raise them. But with any honest reassessment there are bound to be winners and losers, and politicians, unwilling to be unpopular with the losers, resolve the problem by pressuring the assessors to keep the assessments low through manipulation of the millage rates, or by delaying re-assessments for as long as possible – certainly while they are in office. This ‘head in the sand’ solution is well known in England, where a local property revaluation has not been carried out since 1991.

2. Negligent or biased assessment practises

The same sort of pressure was also evident amongst the assessors themselves, who were elected, and therefore subject to a similar situation. In a paper on the History of US Property Taxes, amongst various problems relating to assessments, Glenn Fisher notes,

Another problem arose from the inability or unwillingness of elected l local assessors to value their neighbour’s property at full value. An assessor who valued property well below its market value and changed values infrequently was much more popular and more apt to be re-elected.’ 121

Surrendering to such permanent pressure, although understandable, amounts to negligence. This tendency to make under-valuations applied of course to all property taxes, but where the split-rate tax was concerned there was, according to Sullivan, an additional bias towards reducing the land-value element, effectively undermining the purpose of the 2:1 differentiation. Another weakness of the assessment system was the practice of relying on a ‘base year’ for making assessments. Successive assessments were no more than variations calculated from this base year, and over time became more and more detached from the reality of what was really happening to actual property values. Judge Wettick condemned the indefinite use of the base year system in a ruling in an assessment appeal case in 2007. In the decades before 2001 it is difficult to ascertain when a real market valuation was last carried out in Pittsburgh but various observations indicate that any such valuation had been delayed for very many years. Dye and England note that the January 2001 re-assessment took place ‘several decades after the previous round of property re-assessments.’ 122 Hughes notes that from the 1979 change of ratio ‘the assessments of both land and building values remained essentially fixed in this period and, indeed, for the next twenty years.’ 123

3. The fractional assessment system

The fractional assessment system is explained more fully in Box 2. Basically it allowed jurisdictions to apply only a fraction of the assessed value to determine the millage rates and subsequently how much tax to charge to each householder.. In the case of Pittsburgh, the fractional value had become as low as 25% by the 1990s. Obviously the fractional system worked against any attempt to reconcile assessed with real market values. The ruling by Judge Wettick in 1997 required that assessments should be returned to full market value.124

4. Costs of re-assessments

Opposition to carrying out a re-assessment on grounds of cost would seem to be the feeblest of arguments. It would be like setting up a tax system without being willing to set up any system of administration. Any property tax is dependent on an accurate and honest system of regular re-valuations; a land value tax even more so. Such re-valuations could be financed from the proceeds of the tax. The plea that re-valuations are too costly doesn’t make sense, but nevertheless a 2010 enquiry by the Joint Committee of the Pennsylvania General Assembly on property valuation and re-assessment, reported that when 50 County Chief Assessors were asked, ‘What are some of the reasons why you would not initiate a countywide reassessment? 82% gave cost as a primary reason. Other typical reasons included: public opposition, 34%; unstable market values, 22%; taxing or borrowing to finance the re-assessment, 16% and limited staffing, 14%.125

The assessments problem was undoubtedly the major reason for the eventual abolition of the graded tax, but there were other influences:

Public Hostility

Where householders are concerned a property tax of any kind represents a tax on personal wealth (an existing asset), and has always provoked hostility. They see the total value of their house, which includes the land value, as their primary disposable asset. The majority of people see their home not only as somewhere to live, but also as an asset that increases their overall wealth and security as prices rise in a growing community. If they sell it they may realise a considerable capital gain. If they do not sell it they still remain the owners of an unrealised capital asset.

A land value tax is a tax on part of this asset, the land factor, and is seen by many people, however misguided, as a form of confiscation. The only remedy for this misunderstanding is through education. Explaining how and why the land-value factor is attributable to the community is probably the first step. In 1982 in his article ‘What’s wrong with LVT’, Dick Netzer comments, ‘We live now in a climate of opinion where the taxation of wealth as such, rather than income or expenditure, is basically considered wrong by most people.’ 126 Also: ‘Land value, by definition, is taxation of a form of wealth and it necessarily involves taxation of unrealised capital gains.’ 127

During World War II property taxes were relatively stable throughout the US, but after the war, as austerities were lifted, the economy prospered and property values and assessments rose proportionally. The consequent increase of property taxes gave rise to tax protests and a so-called tax revolt. Many states took measures to limit property taxes, but California’s ‘Proposition 13’ became the most notorious. This was not a protest just against a land tax, but property taxes in general. Amongst other extreme measures, Proposition 13 limited the tax to 1% of real market value and restricted further assessment increases. Glenn Fisher notes that Proposition 13 ‘Proved to be the most successful attack on the property tax in American history.’ 128

But there were consequences that resulted in no benefit for the taxpayers, who had to make up the shortfall in revenues through increases in other taxes. Dan Sullivan notes that in the aftermath of Proposition 13,

While Pittsburgh enjoyed steady land prices in the midst of a building boom, California was consumed by a land-speculation frenzy. Foreign interests acquired more California land within the first 18 months after Proposition 13’s passage than they had accumulated in the entire history of that state.’ 129

Vested Interests

Vested landed interests were of course another cause for the demise of the graded tax, but such interests are predictable and should come as no surprise. Throughout the period there were natural opponents of the tax, the large landholders and property speculators, not least of which were the railroad companies and steel producers who had considerable commercial and political influence. It has been suggested that their influence contributed in holding down the split-rate ratio at 2:1 for many years. 130 On the other hand, as this influence diminished with the decline of heavy industry after World War II, the ratio increases of the 1970s and 1980s were probably made easier to implement. Perhaps the difficulty for LVT advocates is summarized in a comment by Dan Sullivan: ‘The biggest problem is there is no vested interest for land value taxation.’ 131

Academic Influences

LVT advocates tend to believe that anyone in a position of power and influence who opposes LVT must somehow be in the service of some concealed, landed interest, and in many cases that is probably true. But there are undoubtedly those who oppose LVT on purely intellectual grounds, especially academics, who genuinely believe it is a bad idea, in terms of practicality and fairness. These latter probably pose the biggest threat to the advancement of the LVT cause.

The continuing domination of the neo-classical school has already been mentioned, but there have been individual scholars of high repute who have expressed their intellectual opposition to LVT. Well before the arrival of the graded tax Prof. Seligman, who was a pioneer of the income tax in the USA, was a fierce opponent of Georgism. In later years opponents included F. A. Hayek and Murray Rothbard, major figures in the world of economics. The point being made here is that it cannot be assumed that these economists were covertly representing vested landed interests, but, however much in error, were arguing from principles they had arrived at from their own independent studies. Some final observations are worth making:

On Republican / Democrat rivalry

It is reasonable to say the graded tax was never a partisan issue; at its introduction in 1914, it was almost entirely a Republican affair, both those for and those against. At the time of its rescission in 2001, the protagonists, Murphy, for, and O’Connor against, were both Democrats. During his bid to become mayor of New York in 1886, Henry George stood against both Republican and Democrat candidates. On the graded tax Williams comments,

It has been a non-partisan rather than a partisan issue. While determined opposition had to be overcome, Republican and Democratic Mayors and Republican and Democratic councilmen alike have given it strong endorsement.132

Over-promotion of the split-rate option