LVT – FOUND AND LOST

Why was a successful system of LVT abandoned?

- Background history.

- Events leading to abandonment.

- Other suggested reasons for abandonment

- Conclusions and Comment

- Appendices

- Notes

1. Background history

New Zealand holds a rather special status in that it was notably the first country to introduce a system of LVT for raising revenue.1

At the end of the 18th century New Zealand was visited only by whalers and trading ships from Europe and America, which traded with the native Maori. Most contacts were generally peaceful, although some of the European settlers were often uncontrolled and lawless. In 1832 the British government appointed an official ‘Resident’ to introduce some form of law and order amongst the settlers.2 Britain, in its period of empire building, laid claim to the territory, which was considered to be an extension of the Australian colony of New South Wales. In the early 1800s the first colonists from England were Christian missionaries, followed by settlers, some 20 years after the first arrivals at Botany Bay in Australia. The number of settlers increased rapidly and led to disputes with the native Maori, especially over land. The Maori wars with the British arose basically out of disputes over land ownership and encroaching European occupation. In 1840, under the first Governor, William Hobson, the Treaty of Waitangi was agreed with the Maori, in which the Maori were acknowledged as owners of the land of New Zealand. However, in England, in 1846, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, who had been unhappy with the terms of the treaty, issued instructions to lay claim to all the land not directly occupied by the Maori. But the new Governor, Sir George Grey, believing that this would alienate the Maori, devised a scheme whereby the land, rather than being appropriated, would be purchased piecemeal, albeit for paltry prices.

Initially New Zealand was administered as part of the colony of New South Wales, but in 1841 it became a separate colony. In 1852 the colonial period ended when New Zealand was granted self-government. It would seem that under the Grey administration certain progressive ideas about land taxation were brought from Britain. As early as 1849, in Wellington and Marlborough provinces, legislation was proposed allowing for rates to be imposed on the value of land, excluding improvements.3 This was some 30 years before Henry George published Progress and Poverty. However there is no record of any legislation having been acted upon. The first evidence of actual implementation was in the town of New Plymouth, in 1855. In that legislation it was decreed that, if the ratepayers so decided, the rate could be on unimproved land value only.4 This was a clear demonstration of local democracy in action, which established a precedent that was to endure at the local level as a principle for the next 130 years. This local taxation system was adopted generally and continued up to the Rating Act of 1876, when modifications were introduced. It is worth noting the prominent role played by Governor Grey in promoting LVT for New Zealand. He was the Governor General from 1845 to 1853, and later Premier from 1877 to 1879, both periods in which important advances were made for LVT. Grey was a progressive liberal and was no doubt familiar with the new reformist ideas being discussed in the early 19th century. David Ricardo had published his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation in 1817 and expounded his theory of the ‘economic rent’, an idea that Grey no doubt took with him to New Zealand. It is known that prior to his term in office as Premier he met up with John Stuart Mill, a strong advocate of land value taxation.5 Also, in 1871, Henry George published Our Land and Land Policy and in 1890 made a lecture tour of Australia and New Zealand.

Central government revenue in the early years was mainly derived from customs and excise duties and the sale and leasing of land, appropriated or bought from the Maori.6 But as the government started to run out of land to sell, by the 1870s it turned to property taxes, and introduced the Rating Act of 1876. This marked the beginning of national property taxation. But the act was seen by many as retrogressive, in that it adopted the British-type rating system for those communities that had not elected to tax land values. The British rating system taxed the annual rental value of land and buildings combined (known as AV). But this system did not work well in a new country, which did not have the same landlord-tenant structure that applied in Britain, where rental values were easier to assess.7 In New Zealand at this time land was being rapidly acquired and sales were common. It was soon realised that capital values determined by sales were a more accurate way of assessing value for the rates. Capital values also took into account ‘waste’ land being held for speculation, which had capital value but no rental value. Settlers also became aware that levying the rates on improvements, as with the AV system, penalised them for their hard work.

Attempts to introduce a national property tax based only on land values was a protracted affair, which began in 1878 with the Land Tax Act, introduced when Grey was Premier. In 1879 his finance minister John Balance, also an advocate of LVT, introduced a General Property Tax based on the selling value of land, but this was soon repealed by the succeeding conservative National government. In 1882, legislation was passed to replace annual rental valuations with capital valuations, for the reasons mentioned above and also to standardise the method of valuation throughout the country. It also removed the process from the extremely variable local control. But due to local opposition, boroughs that wished were allowed to maintain rental valuations and to make their own assessments.8 In 1891, under a Liberal administration, a combined Land and Income Tax Act was passed which, according to a paper by Barret and Veal, ‘had the intention of breaking up large estates, so property ownership could be more evenly spread throughout the community.’ 9 Attempts to introduce a full land value tax at national level were often thwarted by opposition within the government itself, which as in England had many representatives of land-owning interests. Rolland O’Regan, in his book Rating in New Zealand, describes the slow progress:

In 1894 the Rating on Unimproved Value Bill was introduced as a policy measure. It was passed by the House but rejected by the Legislative Council. The same process was repeated again in 1895. In this year it was carried by an overwhelming majority in the House and defeated by one vote in the Legislative Council. In 1896 the same bill again passed the House. This time the Council withdrew its opposition and it became law.10

The Bill however was hedged in by conditions and applicable to only one part of the rates. As distinct from Britain, the rating system in New Zealand was somewhat more complex. Four kinds of rates had evolved: General rates, General Separate rates, Particular Separate rates and Special rates.11 With the bill finally passed in 1896, three options were provided for assessing valuations, subject to selection by ratepayer’s poll:

- Combined land and improvements assessed by annual rental value. (AV)––the British system

- Combined land and improvements assessed by capital value (CV)

- Unimproved value only (UV)––later re-named land value. (LV)

A further attempt to use land values only for all rates was tried in 1901 but was abandoned due to opposition in the government’s own ranks.12 It was not until 1912 that the Rating Amendment Act was passed allowing for a full tax on land values on all rates. From this point it could be said that New Zealand had complete land value tax systems in place at local and national levels.

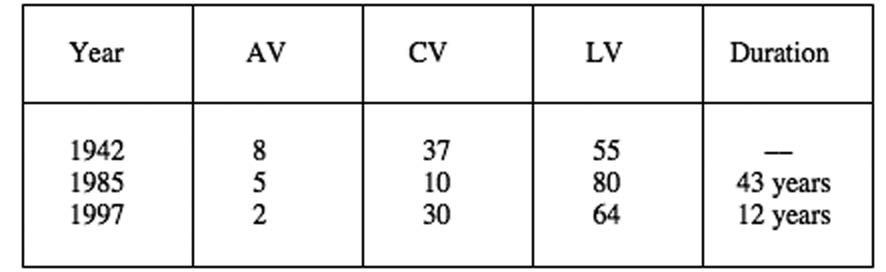

This episode is reminiscent of the struggle that took place in the British parliament after the Liberal government came to power in 1906. The Prime Minister, Campbell-Bannerman, was a keen supporter of LVT but it was another three years before the Liberals were able to introduce a national LVT in the People’s Budget of 1909, only for it to be defeated by the Lords. Unfortunately, in Britain, subsequent events were overtaken by World War 1 and the momentum was lost. This was the period when Henry George’s theories and teachings brought the idea of land value taxation into the mainstream of politics throughout the world. It reached a peak of popularity in the first decade of the 20th century. In New Zealand, the 1912 act continued in force until 1967 when, under a National administration, the local tax on land value once again reverted to only certain rates––a retrogressive step. Perhaps this was the first move towards abolition, which was to culminate in the events of the mid 1980s. It is noteworthy that during the course of the 20th century, at the local level, where there was freedom of choice, the ratepayers preferred the land value tax system (LV), so that by the 1980s the majority of local authorities employed this method. In an article on the history of rating in New Zealand, Robert Keall notes, ‘By 1982 hundreds of rating polls had been held, so that in just 86 years 90% of all municipalities had by poll adopted land value rating, which accounted for 80% of local government revenue.’ 13 The figures of Table 1 are taken from a paper by McCluskey and Franzsen, which show the number of boroughs using the different systems in the 55 years between 1942 and 1997. 14

Table 1. Different Local Tax Valuation Systems: 1942–1997

In a general observation Keall states;

Wherever Land Value Rating applies it has been adopted by poll of ratepayers, representing a lot of work and profound social concern. Wherever Capital or Annual Value Rating applies it has been imposed by Government or Councils, contrary to the express wishes of the ratepayers in almost every case.15

With certain exceptions16 local LVT, assessed through the LV system, was preferred where democratic choice was allowed, but this choice was removed in1988 by the Labour government, which revoked the democratic polls that had kept the local LVT in place for more than 130 years.

The history of the national land-value tax took a rather different turn. Initially it was successful in raising revenue, but perhaps less so than the new income tax, which, as with most governments throughout the world, was gaining in popularity. The land value tax continued well into the next century but from the 1920s went into decline almost as a matter of government policy. On the national tax, Keall comments,

By 1922, the land tax yielded about 10% of the budget. As overseas trade developed and inflation became the accepted means of financing wars or social policy, so land values grew and were protected from any land tax by governments elected to do just that at all costs. Thus by 1989, or 98 years after its confirmation, the land tax yielded only 0.4 percent of the budget and was commonly regarded as an antiquated irritant.17

2. Events leading to abandonment

The early administrators led by Governor Grey would have been conscious of the issues that were of concern to the progressive reformers in the home country. One of the foremost concerns was about the land enclosures and the monopoly power of landed property, which had caused great poverty amongst agricultural workers in Britain. The reason often put forward to justify the land tax was to discourage the formation of large land holdings18 rather than as simply a fair means of raising revenue, but Grey and his administrators were very much aware of the latter. However, regardless of the measures that were put in place, and as happened in most developing ‘western’ countries, the available non-governmental land of New Zealand eventually became privately owned. The new owners were not the aristocrats of old but numerous small holders and powerful speculators and property companies, who instinctively resisted any notions of a land tax. This resistance increased as land values increased, and landholders saw the excellent opportunities for self-enrichment with the growth of the community, especially in the valuable urban centres.

New Zealand was not unique in this sense. All western democratic governments have to a greater or lesser degree been in thrall to, if not in league with, the rich and powerful, who are also usually the landed property owners. Prior to the arrival of universal suffrage, the governments themselves were largely comprised of such owners and therefore resistant to any move that could undermine their interests. These vested interests played a large part in the inexorable decline of the national land tax in New Zealand. After the optimism of the ‘Georgist’ period prior to World War I vested interests prevailed and, mainly through exemptions and under-valuations, the national tax was enfeebled and rendered insignificant in terms of revenue collected. Another adverse influence was the advent of the new income tax in the 19th century, not just in New Zealand but throughout the world. Introduced first in Britain as a temporary measure to finance the Napoleonic wars, it later became popular with governments as a means of raising revenue. Also it had an obvious distinction in relation to means, which was easily understood, and enabled it to be seen as progressive. It also lent itself easily to government control. It arrived in New Zealand with the Land and Income Tax Act of 1891, and from the outset became a growing source of revenue, eventually overtaking all other sources, including the land tax. In their paper of 2012, Barrett and Veal comment that,

From the 1940s, around the world, income tax brought many more people into the tax net and, as a consequence, grew exponentially in importance for government revenue. With the ascendancy of income tax, no incentive lay in formulating a better land tax…. In practice the land tax was undermined by exemptions: in 1982, only five percent of total land value was taxed, ‘agricultural land being explicitly exempted and residential land effectively exempted by the exemption of $175,000 for all landowners. 19

This of course did not affect the local land value tax collected through the rates, which survived and flourished for most of the 20th century in the hands of the ordinary ratepayers, who enjoyed democratic choice up to the 1980s. So in the story of the rise and fall of LVT in New Zealand, the example of the local rates is arguably more instructive where cause and effect is concerned.

So what happened in the 1980s to bring national LVT to an end and severely reduce the effectiveness of the local rates based on LV? After World War II the sequence of political events in New Zealand were very similar to those of Britain: the see-sawing of political control between two opposing main parties, one of the ‘right’ (National) and the other of the ‘left’ (Labour). By 1984 the National party of Robert Muldoon had been in power for nine years and the economy was in crisis. A new Labour government under David Lange came to power in July 1984 with the express purpose of rescuing the situation, and the prime player in this operation was Lange’s finance minister, Roger Douglas, who was to become instrumental in the demise of LVT. Douglas, supposedly on the left of the political divide, and ironically, a former member of the New Zealand Land Value Rating Association,20 introduced a series of right- wing policies in his radical solution to the crisis (see appendix 1). His neoliberal measures owed much to the neoclassical school of economics, which had always been basically opposed to any Georgist principles (see appendix 2). An account by the journalist Simon Louisson of the New Zealand Press Association records,

The United States was in the grip of Ronald Reagan’s free market Reaganomics while Margaret Thatcher was also pursuing Chicago School of Economics’ monetarist policies. But neither went as far as New Zealand under Finance Minister Roger Douglas…. 21

An article on the website New Zealand History.net describes the events in 1986:

Radical change came thick and fast: deregulation, privatisation, the sale of state assets, and the removal of subsidies, tariffs and price controls. GST (value added tax) was added to the mix in 1986. This ‘regressive’ tax hit the poorest the hardest, because people on low incomes spend a higher proportion of their money on basic goods and services than the better-off.22

Among these reforms the continuation of LVT stood little chance. The National LVT had already become insignificant in terms of revenue and was abolished in 1991. Robert Keall comments, ‘The tax had become a political football. So to pre-empt a Conservative National opposition promise to abolish the tax, the Labour government did just that.’ 23

On the local rates he notes, ‘Since the time of restructuring in 1989, combining urban with rural areas, the 90% of municipalities which by poll had adopted land-value rating has been reduced to about 40%.’ 24 And also, ‘In the Rating Powers Act of 1988–89 the government withdrew the traditional right to demand a poll.’ 25

Henceforth it became the local authorities rather than the people that decided which form of rates to adopt. Between 1989 and 1999 many local authorities switched from LV to CV, most of which were in high-value urban areas.26 The local rates based on unimproved value (LV), which had always depended on the popular polls for their continuance, suffered a great set back when this democratic process was revoked by the government in 1988.27 The Labour government made it clear that it preferred valuations based on capital values, which favoured the new growing urban centres with high land values. Accordingly most of the major cities of New Zealand had reverted to capital-valuation rating by the end of the 1980s.28 Thus, in New Zealand, within a few years in the 1980s, 95 years of national LVT was lost and 133 years of local LVT severely diminished. In an article on the Conversation website of November 2015, Dumienski and Ross Smith, commenting on the present state of Australian state land-value taxes and local rates in New Zealand, stated that ‘over the last century these taxes have become significantly debased due to the influence of various interest groups that secured exemptions or low rates.’ 29

Another reason for the decline of local LVT was through the amalgamation of adjacent boroughs. During the whole of the 20th century amalgamations of local authorities took place in the name of efficiency, especially where authorities had the same rating system. However some amalgamations were exploited to get rid of LV. O’Regan, although a supporter of the principle of amalgamations, mentions several such instances and comments, ‘The promoting of an amalgamation to get rid of unimproved value (LV) has been a well tried technique.’ 30

Local rating based on land values continues today with certain councils, but its effect is much reduced through exemptions, thresholds and the growing practice of charging direct fixed taxes for particular services.31

3. Other suggested reasons for abandonment

Here are some further reasons for the abandonment of LVT, proffered in other academic papers and articles:

Robert D. Keall, Former finance executive, investment broker, and leading figure in the New Zealand Land Value Rating Association, commenting on the aftermath of the 1896 Land Value Rating Bill:

Despite the rapid success thereafter at the hands of ratepayers there remained a crafty opposition who constantly tinkered with it, confusing even the most assiduous student.32

And on the later events of the 1980s:

The assault on Land Value Rating, coincidental with the sale of natural monopolies, exemplifies a contrived co-ordination of: a. relieving natural resources of any public charges to enhance the privatised unearned speculative value. b. privatising natural monopoly profits – both wrongfully, at the expense of the public sector.33

He encapsulates what is perhaps one of the most potent sources of opposition to LVT when he says, ‘Because land (and thus land value) is perceived as sacrosanct private property, land-value charges are too often seen as an invasion of private property.’ 34 Also, on the political aspect,

‘It indicates an infiltration of the Labour party by the World Bank to neutralise effective radical opposition to the new right global agenda of privatising natural resources: i.e. owning the Earth and privatising the rent.’ 35

Jonathan M. Barrett, senior lecturer in taxation, Victoria University, Wellington, and John A. Veal, principal lecturer, Open Polytechnic of New Zealand, in a paper entitled Land Taxation: a New Zealand Perspective:

Unfortunately, for its proponents, LVTs are not generally understood. Indeed even at the height of enthusiasm for the Georgian (sic) single tax, his sophisticated arguments were understood by only a few in New Zealand and accepted by fewer.36

Barry F. Reece, lecturer in the School of Building, University of New South Wales, former tax advisor to NSW Treasury. In a paper entitled ‘The Abolition of Land Taxation in New Zealand: Searching for Causes and Policy Lessons’, acknowledging his sources from S. L. Speedy of the New Zealand Institute of Valuers, Reece writes,

Those who are affected see it as a discriminatory wealth tax.37

Also:

The removal of the principle residence from the tax base was made in the 1976 Land tax Act…the circumstances in which the principle residence was freed from land tax partly foreshadowed the circumstances surrounding abolition in 1991.38

The Taxation Review Committee of 1967 recommended that land tax be abolished, pointing out that the revenue from the tax had dwindled to a very minor proportion of total revenue.39

Reece offers five possible reasons for the abolition of the tax:

- The tax was unpopular with lobby groups of land-tax payers.

- The tax was unpopular with Labour Party reformist politicians concerned with advancing further the major reform of the New Zealand tax system associated with the introduction of GST (VAT).

- The bureaucracy was dissatisfied with having an incomplete base for land taxation, as agriculture and principle residence were excluded, and preferred its complete abolition to continuation of the existing emasculated business land tax.

- Local government wanted abolition so it could expand its tax effort to fill the tax vacuum that would be created.

- The New Zealand economy had matured to the stage where land tax could be removed.40

With reference to item 2: In the 1990 budget speech, the year before abolition, the Labour government claimed that ‘substantial exemptions meant that the majority of land in New Zealand remains outside the tax base, giving rise to distortions and unfairness in its application.’ 41 Reece also states that the Labour Party believed that ‘Abolition would appeal not only to lobby groups and the party faithful, but to the wider electorate.’ 42

Perhaps reason 5 is the most surprising. Reece appears to be saying that mature and sophisticated economies, at some point of development, can discard a land-value tax as being only suited to more basic undeveloped (agrarian) economies. Reece does state that the most convincing reason is the second, where ‘the action of reformist politicians was paramount.’ 43

We have to accept that there will always be a strong opposition from those whose power derives from land ownership. Such opposition never dies and will take any opportunity to disparage LVT at any time. An example of this is shown in an interesting article entitled ‘Taxation of Land––The New Zealand System’ that appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald of April 14, 1932.44 The writer (identifiable only as ‘HHB’) expresses his vehement opposition to LVT in the following comments:

The land tax…may justifiably be written down as an effort of inexperienced politicians that has been proved by the test of time to be a complete failure. New Zealand, after 54 years of experiment recognises this, and the Taxation Commission of 1925 recommended that as the land tax had failed to achieve the only objective which justified its existence, it should be abolished. As a means of raising revenue the land tax is the negation of the cardinal principle taxing according to the ability to pay.

He mentions several times that the prime objective of the tax was to break up large land holdings––an aim that was never achieved. Referring to the later experience of Australia after 1910 he comments,

It had been conclusively demonstrated that the taxation of land was not an effective means of forcing the sub-division of large estates; and this was the intention of the Australian legislators. New Zealand, the pioneer of this form of impost, realises its inefficiency and its flagrant injustice.

It is curious that he made these comments at a time when the land-value based taxes at local level in New Zealand were gaining ground through the popular vote. Earlier in the article he does admit that the tax ‘provides one item of revenue which can be reliably estimated by the treasury.’

4. Conclusions and comment

The question still remains. Why did New Zealand lose its grip on LVT? For a great number of years it seemed to be very well established, at least at the local level. From the foregoing account it would appear that in the case of the national tax, it was largely a matter of central government indifference or neglect, even downright hostility. In the case of the local tax, in the final years it appeared to be more a matter of overt ideological government opposition. The national tax was allowed to die slowly over a long period, whereas the local rates, after a long period in the ascendant, went into abrupt decline from 1985 onwards. In both cases the opposition to LVT stemmed from the governing authorities, not from the people.

The National Land Tax

How does one account for this government hostility? Governments are always searching for ways to raise revenue, and from 1896 the national land tax was ‘for several years the largest source of government revenue and arguably an important factor contributing to New Zealand’s once famed egalitarian character.’ 45 But as mentioned earlier, by 1989 the tax had reduced to only 0.4% of the budget.46 The national land tax was introduced at the time that the new enthusiasm for the radical Georgist movement was gaining momentum worldwide and which continued up to the outbreak of World War I. After the war the earlier generation of Georgist reformers had died off and different ideas were in the ascendant. As in Britain the Liberals, who had traditionally been the advocates of LVT, were displaced by the Socialists, who had other ideas about the redistribution of wealth, which included nationalisation. Also the income tax, which appeared to cast its net ever wider, was becoming more popular with governments. In the US the neoclassical economic philosophy was gaining ground and inexorably spread its influence throughout the world. The neolassical economists held a view that was diametrically opposed to that of the Georgists, especially over the issue of land, but they were supported by the powerful landed interests and eventually came to dominate economic thought, which continues to the present day. In the inter-war years the original principles of LVT were largely forgotten. After World War II the revenue from the national land tax continued to decline so that by 1967 a government taxation review committee recommended its abolition, quoting the insignificant amount of revenue it brought in, and also the old complaint that it was ineffective in breaking up large land holdings––this reason for LVT still being proffered rather than that of raising revenue. 47 Perhaps this review signified the beginning of the end for the national land tax. In 1982 another government report noted that the land tax had ‘no perceptible redistributive effect’ and was ‘not an adequate indicator of the taxable capacity provided by wealth.’48

And so it would seem that government opposition to the land tax was already under way before the later events initiated by Roger Douglas (see box 4). In the 1970s and 80s the neoclassical school of thinking dominated world economics, including the central banks, the IMF, the World Bank and the universities. This was the period that saw the rise of ‘Reaganomics’ in the Reagan–Thatcher era hallmarked by deregulation, privatisation and the promotion of neoliberalism. It was at the height of this world movement in 1984 that the new Labour government came to power in New Zealand and under the finance minister Douglas, carried out the drastic right-wing policies described earlier. For those on the right Douglas was the hero that rescued New Zealand from the crisis––but at what cost? A land value tax could only survive where there was a controlling authority that understood the principle––of the economic rent––that lay behind it, and unfortunately in the later years in New Zealand that understanding was lacking. In their paper, Barret and Veal note that ‘To a great extent successive governments allowed the tax to fail.’ 49

The Local Rates

It has to be noted that local taxes, in whatever form, only raised a small proportion of total revenue throughout the period. In 1874, revenue raised from the rates represented only about 7% of the total of local and central government revenue combined; similar to the proportion in the 2000s.50

In the early years of settlement it was the administrators that introduced the idea of land value taxation, freshly imported from the progressive political thinkers in Britain. No doubt the administrators saw the opportunity of establishing a system that might avoid the mistakes and injustices of the old country. The system was imposed initially from the top, for ideological reasons, and was gradually accepted (and later preferred) by the ratepayers. This fact in itself is interesting. It is doubtful that these early settlers had suddenly become knowledgeable about the Ricardian principle of the economic rent. No doubt they soon realised it was beneficial to them in that they were not penalised for making improvements, but it is more likely they simply did the arithmetic, looked at the bottom line and saw which system gave them the best deal. For the next 130 years, by virtue of the poll, they were able to decide which system suited them best. O’Regan notes that ‘Wherever rating on the unimproved value has been adopted it has been adopted by poll.’ 51 But sometimes the ratepayers changed their minds. Change of status by poll could be volatile. Hawkes Bay County changed from CV to LV in 1921. In 1928 it changed back to CV, then in 1931 changed again to LV, which was then retained.52

In 1973, in support of the LV system, O’Regan was able to say that ‘The Land Tax has been in force for at least eighty years and there is not a property in the country subject to the tax which has not been purchased with this impost upon it.’ 53

Land value tax at the local level was an undeniable success in New Zealand. It was tried and tested over a long period of time, but as with freedom itself, as the old adage goes, it is only appreciated when lost. The League for the Taxation of Land Values, formed in 1943, tried to maintain a public interest, but as Keall notes, ‘Over the post-war boom years interest flagged, members died and LV rating became almost universal and largely taken for granted.’ 54

So one can probably say that apathy was another factor contributing to the general eclipse of LVT.

Appendix 1. Notes on Roger Douglas

Roger Douglas played a key role in the demise of LVT in New Zealand. He was the Finance Minister from 1984 to 1988 in the Labour government led by Prime Minister David Lange. His astonishing transformation from a supposedly left-wing Labour politician to an exponent of hard-right policies is revealed in some of the quotations that follow. His radical policies, which became known as ‘Rogernomics’ after the election of 1984, were successful to the extent that the Labour party was re-elected in 1987. But they finally led to disagreements with Lange and his standing down in the election of 1990. He had become a Labour MP in 1969 and served in the Labour government of 1972 to 1975, which, because of its mishandling of the economy, lost the election of 1975. The Labour party remained in opposition till 1984, when it returned to power because of the even worse mishandling of the economy by the incumbent National government.

Douglas was critical of the previous policies of his own party and was initially supported by Lange, who saw him as a moderniser, but ‘By the end of 1983 his thinking had shifted markedly to the economic right.’ 55

Where policies were concerned Douglas also had allies in the government treasury whose view of economic policy was ‘neoclassical and monetarist, and used commercial criteria as the basis for decision making.’ 56 Although Lange was initially in agreement with Douglas’ policies, by 1986 he was having doubts, and the relationship later became strained. At the end of 1988 Lange dismissed Douglas as finance minister, but by then the legislation had been passed. Douglas did not stand at the election of 1990, which Labour lost, but the succeeding National government continued his policies. In 1993 Douglas co-founded a new party, the Association of Consumers and Taxpayers (ACT), with the purpose of pursuing his earlier policies. He entered parliament again in 2008 for the ACT party, which allied itself with the National party. In 2011 the ACT party included in its manifesto an ungraduated flat-rate income tax, reduced welfare spending, more defence spending and charging interest on student loans. Douglas retired from active politics in 2011.

In 1993, he set out his policy aims, one of which stated, ‘The abolition of privilege is the essence of structural reform.’ 57 But it is questionable whether this principle was ever respected. In an article summarising an interview with Douglas, the journalist Bridget Gourlay comments, ‘Some credit Sir Roger Douglas with single-handedly saving New Zealand from ruin. Others blame his policies for causing a huge gap between the rich and the poor, one that still exists today.’ Also she notes, ‘Serious money was made as the markets de-regulated. Serious poverty was caused as factories around the country shut down.’ 58

Prime Minister Lange often disagreed with the extremity of Douglas’ measures. In 1996 he is recorded as saying, ‘For people who don’t want the government in their lives this has been a bonanza. For people who are disabled, limited, resourceless, uneducated, this has been a tragedy.’ 59 Later, Douglas is recorded as saying, ‘Socialism has failed the poor.’ 60

It is easy to cast Douglas as the villain of the piece, and there is no question that he led the vanguard in the new right movement, but he did not act alone. He no doubt represented the political sentiments that prevailed at the time as a consequence of the economic crisis in New Zealand and the spread of neoliberalism worldwide.

Appendix 2. Neoclassical Economics

Perhaps the most effective continuous force ranged against LVT throughout the world has always been the neoclassical school of economic thought. Neoclassical economics arose in the US in the late 19th century almost concurrently with the rise of Georgism but represented a very different ideology, where the status of land was concerned. Georgism continued the classical economic view that there were three basic elements leading to wealth creation which were separate and distinct: land, labour and capital. Henry George made these distinctions very clear and pointed out that the return to land was rent, the return to labour was wages and the return to capital was interest.61

The neoclassical view was that land was merely another form of capital and therefore only the two elements, labour and capital were significant. This view was advantageous for landowners and large industrialists who were able to claim their rightful return on capital––which now included land. The political philosophy of Henry George was seen by the rich and powerful as a direct threat to their power base. In his book The Corruption of Economics, co-authored with Fred Harrison, Mason Gaffney comments,

Henry George and his reform proposals were a clear and present political danger and challenge to the landed and intellectual establishments of the world. Few people realise to what degree the founders of neoclassical economics changed the discipline for the express purpose of deflecting George and frustrating future students seeking to follow his arguments.62

This opposition to George was seriously organised in the US. In an article on the Wealth and Want website, William Batt gives an account of the influence of the railroad and land ‘barons’ who, through their financial sponsorship of the major universities, were able to determine important placements of academic positions favourable to neoclassical economics. 63 The early reformist movement in the US, in which Georgism played a leading part, became forgotten in the tumultuous events of the first half of the 20th century: two world wars and a major economic depression. Inevitably the neoclassical school prevailed and came to dominate economic thought throughout the world.

The neoclassical movement became centred in the US at the university of Chicago, and became known as The Chicago School. One of its leading exponents was the economist Milton Friedman, quoted in the Introduction to this book as supporting the idea of LVT. How does one explain this seeming paradox? Having watched the video of the lecture in which he makes his statement of support 64 my only explanation is that Friedman was praising LVT because it is efficient and difficult to avoid––a view that most economists hold. However, in another interview 65 he advocates the use of digital currencies because they would make it more difficult for the government to collect taxes generally, a seemingly libertarian view that appears to contradict his earlier position. For me this remains a mystery.

The neoclassical school later evolved into neoliberalism, that puts its faith in free markets, deregulation and privatisation and which still holds sway today. But in recent years there have been signs that the neoclassical/neoliberal orthodoxy is being questioned as inequalities become more acute and the current system is seen to be working only for an ever-smaller elite. The practice of LVT in various forms is still alive in the world, especially in Pennsylvania in the US, and there is evidence of a revival of interest amongst economists, journalists and academics worldwide.66 At the political level, recent evidence of this revival comes from Germany where, in November 2020, the state of Baden-Württemberg elected to introduce a land-value tax system in 2025.67

_____________________

Notes

- Robert D Keall, Chapter 26, p. 425 of Land Value Taxation Around the World, edited by Robert V Andelson, Blackwell Publishers. 2000

- https://www.lonelyplanet.com/newzealand/narratives/background/history

- Rating in New Zealand, Rolland O’Regan, p.21, para.1, Baranduin Publishers 1985

- Ibid. p. 21, para. 2

- Keall/Andelson, Land Value Taxation… p. 422, para. 5

- Te-ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Govt. revenue 1840–1890. Graph. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/graph/21529/government-revenue-1840-1890

- McCluskey & Franzsen, ‘LVT A Case Study Approach’. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, working paper, 2001, p. 7, para. 1 http://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/100Land-Value- Taxation

- O’Regan, Rating… p. 25, para. 1

- Barrett & Veal, ‘Land Taxation: a New Zealand Perspective.’ eJournal of Tax Research, UNSW, paper, 2012, p. 576, para. 2 http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/eJlTaxR/2012/25.pdf

- O’Regan, Rating… p. 26, para.2

- Ibid. p. 26, footnotes

- Ibid. p. 27. para. 2

- Robert D. Keall, ‘A Short History of the N.Z. Land Value Rating Association.’ Resource Rentals for Revenue, 2008. p. 2, para. 7 http://resourcerentalsrevenue.org/nz- association-short-history.html

- McCluskey & Franzsen, p. 74

- Keall/Andelson, Land Value Taxation… p. 427, para. 2

- O’Regan, Rating… p. 79, para. 2

- Keall/Andelson, Land Value taxation… p. 423, para. 1

- Dumienski & Ross Smith, ‘Land Tax Best Fix for Housing Crisis,’ New Zealand Herald, Nov. 2015. p. 1, para. 6 http://www.nzherald.co.nz/business/news/article.cfm? cid=3&objectid=11543819

- Barrett & Veal, p. 578, para. 2

- Keall/Andelson, Land Value taxation… p. 420, para. 2

- http://www.sharechat.co.nz/article/07c29b10/opinion-the-rogernomics-revolution-20- years-on.html

- New Zealand history: ‘Goods and Services Tax Act comes into force,’ Oct.1986, p. 1 http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/the-goods-and-service-tax-act-comes-into-force

- Keall/Andelson, Land value taxation… p. 423, para. 4

- Robert Keall, ‘A Short History…’ p. 3, para. 7

- Ibid. p. 3, para. 4

- McCluskey, Grimes & Timmins, ‘Property Taxation in New Zealand’. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, working paper, 2002, p. 19, para. 4, p. 20, para. 3 http://www.lincolninstdu/pubs/681Property-Taxation-in-New- Zealand

- Robert D. Keall, ‘A Short History…’ p. 3, para. 4

- Ibid. p. 3, para. 3

- The Conversation: Dumienski & Ross Smith, Nov. 2015, p. 2, Para. 4 http://theconversation.com/a-land-value-tax-could-fix-australasias-housing-crisis-49997

- O’Regan, Rating… p. 51, para. 2

- Dierdre Kent website: ‘Why Land value Taxes?’ Item 17 http://www.slideshare.net/deirdrekent/why-land-value-taxes

- Keall, ‘A Short History…’ p. 2, para. 2

- Ibid. p. 5, para. 1

- Keall/Andelson, Land Value Taxation… p. 436, para. 2

- Keall, ‘A Short History…’ p. 5, para. 2

- Barrett & Veal, p. 586, para. 3 (citing Steven C. Bourassa and Paul Goldsmith)

- Barry F. Reece, UNSW paper 2003, ‘The Abolition of Land Tax in New Zealand: Searching for Causes and Policy Lessons’, p.227, para. 2 http://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage? handle=hein.journals/austraxrum10&div=18&id=&page=

- Ibid. p.227, para. 3

- Ibid. p.230, para. 2

- Ibid. p.236, para. 2

- Ibid. p.238, para. 3

- Ibid. p.240, para. 3

- Ibid. p.241, para. 5

- http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/16855914

- Dumienski & Ross Smith, p. 1. para. 9

- Keall/Andelson, Land Value Taxation… p. 423. para. 1

- Barrett & Veal, p. 577. para. 3

- Ibid, p. 577, para. 3

- Barrett & Veal, p. 578, para. 2

- Te-ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Taxation: 1840 to 1880s: p. 1, para.8. http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/taxes/page-1

- O’Regan, Rating… p. 27. para. 4.

- Ibid. p. 79, para. 2

- Ibid. p. 84, para. 3

- Robert Keall, A Short History, p. 1, para. 4

- Brian Easton ed. The Making of Rogernomics, Auckland University Press, 1989. pp. 19–20

- Ibid. pp. 64, 114

- Brian Easton, ‘Economics and Other Ideas behind the New Zealand Reforms.’ P. 2, para. 8 https://www.eastonbh.ac.nz/1994/10/economic_and_other_ideas_behind_the_new_zeal and_reforms/

- Magazines Today, Sir Roger Douglas: Bridget Gourlay interview, p. 1, paras. 1 & 8 http://magazinestoday.co.nz/sir-roger-douglas/

- Ibid. p. 1, para. 9

- Ibid, p. 2, para. 3

- Henry George. Progress and Poverty, pp. 112–113

- Gaffney et al., The Corruption of Economics, p. 29

- William Batt, ‘How the Railroads Got Us On The Wrong Economic Track’, p. 4, para. 5 http://www.wealthandwant.com/docs/BattHTRGUOTWET.html

- See video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yS7Jb58hcsc

- See Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j2mdYX1nF_Y

- Refer to: Land Value Tax Guide–Supporters: https://landvaluetaxguide.com/category/individuals/

- https://www.hgsss.org/event/land-value-tax-breakthrough-in-baden-wuerttemberg-germany/