Politicians are always averse to any change in taxation that will create losers who will cost them votes, so they tend to resort to indirect taxes where no obviously disadvantaged group can be identified. Although any change to LVT would create winners and losers, in any part of the economy where land was involved, it is arguably the effect on homeowners that would give politicians most concern. The losers would be those who hitherto had been the winners over several decades; those who had enjoyed the benefits of increases in their asset wealth completely fortuitously without any effort on their part. Under LVT this advantage would be arrested and gradually reversed over time, with a reduction of house prices. This would undoubtedly create opposition from those who have got used to the idea of ever increasing unearned asset wealth and who would not wish to see this advantage eroded. The opposition to LVT would be considerable, not only from these homeowners, but also from the government itself, as Josh Ryan Collins and co-authors note: ‘No government wishes to see the damaging effects of a fall in house prices, especially when almost two-thirds of voters own a property.’ 1 The winners would of course be renters and those homeowners who have seen their house values remain static or even go down over the same period, due to being in areas of low or declining land values.

The updating of valuations for any property tax, LVT or otherwise, will always create winners and losers, and the amount of any change, for better or worse, is naturally less where the valuations are frequent. This helps to make the change more acceptable to the losers. The more infrequent the valuations, the greater will be the impact of any change, giving rise to the greater likelihood of protest from the losers. Any updating of the current council tax valuations, neglected for so long, is now viewed with horror by most politicians, knowing full well the impact this would have on the losers in their own constituencies. And so the situation continues to get worse with each year that passes, and it has now got to the point that any such revaluation would itself require a transition period. Also, those in high-value properties––the wealthy and influential––who would stand to lose the most due to any correction would form a serious opposition, especially where any update was connected to the introduction of LVT. In Andelson’s book Land Value Taxation Around the World, Garry Nixon notes that the land value assessments that operated in Canada in the early part of the 20th century became up to forty years out of date, and whenever attempts were made to correct this situation ‘the landowners (who share a marked disinclination to share their new found gains), band together and lobby for the status quo.’ 2

As mentioned in Part 2, item 2, it is generally accepted that the introduction of LVT at a local level is initially more practicable than at the national level. One of the options in the UK is through reform of the council tax which, I suggest, could be done in a way that addresses this issue of winners and losers. (The deficiencies of the present council tax system are described below).

Currently the council tax is based on the capital value of the property (land and building combined), so the first step would have to be a new valuation where building values are separated from site values. From this point, there would be two possibilities, both the same in principle but different in degree: one a change to a full 100% LVT, the other to a partial LVT based on the split-rate system practised successfully in several cities in Pennsylvania, US.

Under the 100% system the new revaluation (which in itself could take a year), would reveal the discrepancies due not only to the new calculations for site values, but also to the consequences of the many years of previous neglect. These discrepancies are likely to be significant, and it would be important to inform all taxpayers in advance of the new dispensation and the estimated future tax liabilities––over a transition period of say 10 years. Assuming overall revenue neutrality, I would propose that in the first year nothing would change, but taxpayers would be served notice of their current council tax liability as well as the new liability under LVT––in side-by-side documents. The figures would show the difference between the two levies, divided into ten equal parts, to be added or subtracted as appropriate over the ten-year period, starting in the second year. At the end of the 11th year a full LVT system would be established, and the council-tax calculations could be discontinued. The transition period would avoid any abrupt or disruptive changeover. Those who are to gain from the change would be obliged to defer their gain over the period, and those who are to lose, would have their loss eased over the same period. In this way the winners would be compensating the losers and the figures would be clearly shown in their tax bills every year. It is important that such compensation should be visible, immediate and personalised, and not in the form of some vague promise that other taxes would be reduced in the future.

The second system would be similar in application to the first, except that the ultimate aim would be to arrive at a proportional imposition of the tax divided between the building and the site (say 40/60% or 20/80%), so there would still be some element of tax on the building. This of course is a compromise, but it would make the transition easier, especially for the losers, and would leave open the option of applying a 100% LVT in the future––if it was seen by the taxpayers to be working beneficially. And this is the crucial point. It has to be seen to be working for the majority. I am inclined to favour this second course as being more practical and more flexible. It is important to get the taxpayers onside, otherwise the whole experiment could founder. Another considerable advantage of adopting this second option is that we in the UK could benefit from the experience of the cities in Pennsylvania, which have practised the split-rate system successfully for many years.3

If LVT were to be introduced at the national level, dealing with the issue of winners and losers would be magnified considerably, and a similar formula would need to be devised where the principle of winners compensating losers over a transition period would still apply.

The Council Tax Deficiency:

Local revenue for residential properties is currently collected through the council tax, which a great many commentators report is grossly inefficient and unfair. Apart from the neglect of regular valuations, one serious criticism is with the banding system. In England, there are eight bands based on what the property would have been valued at in 1991, ranging between the minimum (band A at £40,000) to the maximum (band H at £320,000). Each council is allowed to set its own rates within these bands. In poorer areas the greater number of properties lie in bands A to D, whereas in wealthier areas they tend to be in bands D to H, which means that wealthier areas can raise the same amount of revenue from a lower than normal rate, mainly from high-value properties. This is seen as unfair. The inequity of the system was summed up in an article by a councillor from Kirklees in West Yorkshire, comparing their situation to that of Westminster:

‘About 60% of our homes are in band A … if all their houses are in band H, then they only need to set their tax at a fraction of ours and make the same amount of money.’ 4

Within London, in 2019–20, a house in band D in Barking and Dagenham paid a council tax of £1,556, more than double the tax of £752 for a band-D house in Westminster.5 It is often the case that a multimillion-pound band-H house in a high-value central location will be paying less council tax than a band-D house in a low-value location.

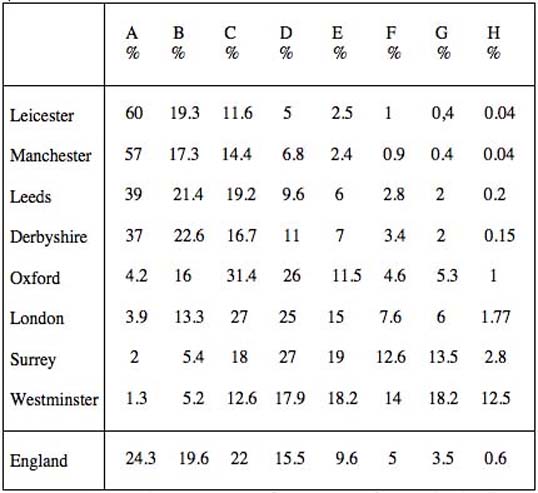

Table 2 shows comparative percentages of the numbers of properties in the tax bands for different cities and counties in England in 2019.

Table 2 Comparative percentages of the number of properties, in all tax bands for different English cities and counties, 2019 (Source: Valuation Office Agency, Table CTSOP 1.0, Sept. 2019)

These anomalies arise under the present system where the tax is based on capital values, with an arbitrary cap on maximum payments, disregarding the enormous variations due to location. Were the tax to be based on location values only, these variations would be taken into account, resulting in a higher imposition in the high-value locations. For that reason, the LVT system would be fairer. The total revenue accruing to the council would amount to whatever was required to meet its commitments, starting from the highest location values and decreasing according to the measure determined by decreasing site values. The council would set the rates within these site-value parameters on a sliding scale rather than a banding system. The bases of the current council tax and a proposed land-value tax are very different. Within the constraints of the planning laws, a land-value tax is not concerned with what is on the site, but only with a payment for the use of it.

References:

(1) Josh Ryan Collins, Toby lloyd & Laurie Macfarlane, Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing, Zed Books Ltd. 2017, p.147

(2) Garry B Nixon / Andelson, LVT Around the World, p.67.

(4) https://www.examinerlive.co.uk/news/west-yorkshire-news/kirklees-council-tax-three-times-16021996

(5) http://www.bexley-is-bonkers.co.uk/local_taxes/league_table/2019.php